Todd:Chem3x11 ToddL2

Chem3x11 Lecture 2

This lecture is mainly about cyclohexane, and what it looks like with and without a substituent.

(Back to the main teaching page)

Key concepts

- Cycloalkanes have 3D structure

- Cyclohexane has a chair conformation and a less stable boat conformation

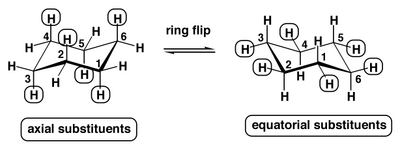

- Dynamic movement of cyclohexane causes "ring-flipping" which swaps axial and equatorial substituents

- Substituents on the cyclohexane ring change this ring-flipping behaviour

Cycloalkanes

Basic Types of Cycloalkanes

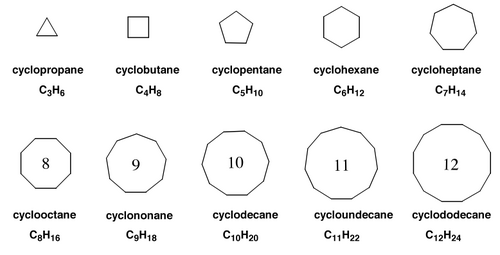

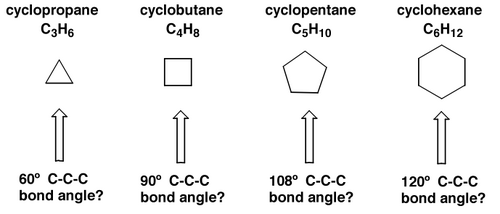

Cycloalkanes are, as might be expected, cyclic alkanes, with general formula CnH2n, with a logical naming system:

Naming Substituted Cycloalkanes (revision from Y1)

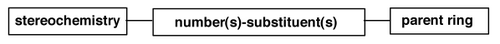

The nomenclature is like any other organic molecule:

...and you name the molecule right to left. i.e. stem (parent) first, then the subsituents, then the stereochemistry. Let's try one:

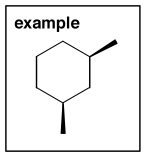

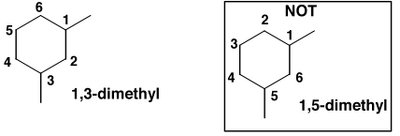

The parent ring is cyclohexane. There are two methyl groups hanging off the ring, and we have to specify unambiguously where they are. Take one of them as number "1" and number the other atoms around the ring in order, keeping the numbers as low as possible, i.e.:

The stereochemistry is cis because the two methyls are on the same face of the ring (coming towards us). Remember that cis and trans isomers can only be interconverted by breaking bonds - they are configurational isomers.

So the full name of this molecule is cis-1,3-dimethylcyclohexane. We write the name left to right, but we devised the name right to left.

Why Cycloalkanes Aren't Flat

sp3 carbon likes to bond with angles of about 109°. If we look at cycloalkanes (they way we draw them on paper), we see that there is a problem - the structures must be strained.

The angle strain for each of the above structures would be 49°, 29°, 1° and 11° respectively. Does this correspond to reality? No, because molecules are not flat. In reality cyclohexane has zero angle strain because it buckles out of the plane and ends up looking like a chair (sort of). We call this the chair conformation. The ring can actually adopt all kinds of shapes, but the global minimum energy is this chair conformation.

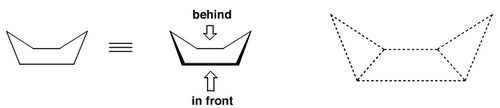

There's another conformation that is often seen, but which is higher in energy, and that's the boat conformation:

Despite the freedom to buckle and move, remember that rings have far less conformational freedom than their acyclic counterparts.

Axial and Equatorial Substituents on Cyclohexane

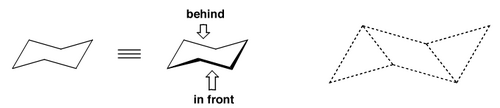

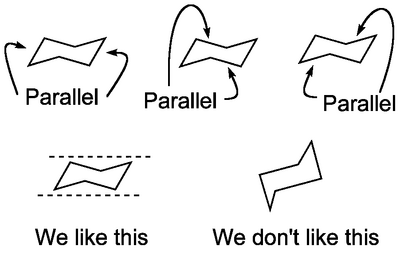

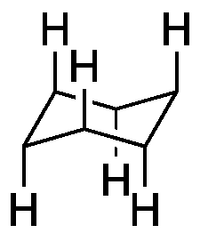

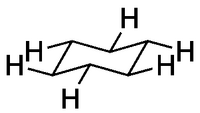

This may seem like an art class, but it's very important to be able to draw groups attached to cyclohexane. The first thing to get right is the ring itself. Let's start with the chair conformation, below. Now if we want to draw cyclohexane from the top, we just draw a regular hexagon, but if we want to indicate its real 3D shape, we draw it from the side:

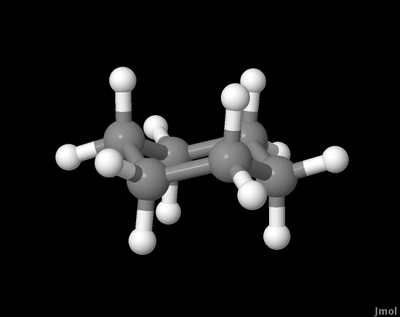

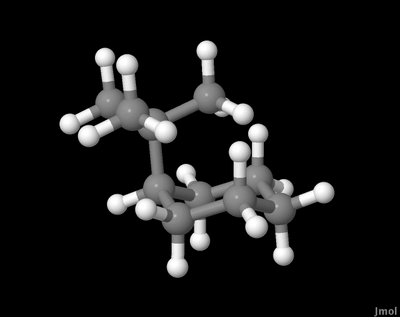

Notice the way each line is parallel to another. And that some of the vertices actually lie on the same imaginary horizontal line. If we actually model cyclohexane on a computer (or build a model in our hands) it looks like this:

You'll notice the substituents are of two types - ones that stick up/down vertically, and others that appear initially to be at odd angles. Let's look at these in turn.

Axial Substituents

These H's are all equivalent in cyclohexane. We draw the bonds vertically. Notice how they alternate between up (when the ring points up) and down (when the ring points down). Notice how we break the line indicating the C-H bond at the back, to show that it's at the back.

Equatorial Substituents

These substituents point out from the ring. Notice how the lines are parallel to a C-C bond one bond away.

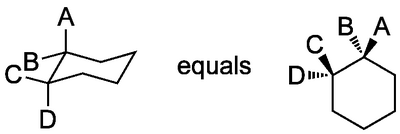

The convention is that if we draw a cyclohexane flat, we're viewing it "from above". It's important to see how the stereochemistry we draw with wedged and dashed bonds translates into 3D:

...i.e. substituents that are "up" in the usual representation on the right in the scheme above are not necessarily axial. We'll come to this in more detail when we talk about how the ring moves.

The Boat Conformation of Cyclohexane

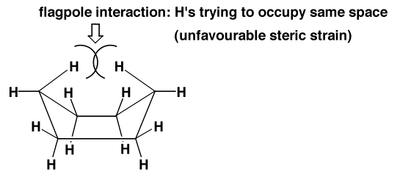

While cyclohexane's chair conformation has two different kinds of hydrogen atom environments, the boat conformation has four. The clash shown below helps explain why the boat conformation is less thermodynamically favoured.

Why the Chair Conformation is Preferred

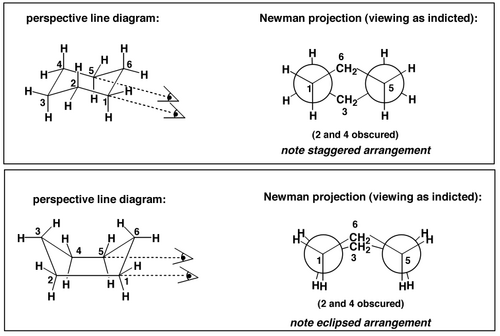

As we can see from Scheme 13 there is a steric clash in the boat conformation. That's not all. There is another kind of strain. It's not angle strain - all the bonding angles in either the chair or the boat are 109°. It's a torsional strain. To see this we can draw Newman projections of the two conformations, like this:

Notice the eclipsed C-H bonds in the boat conformation - this causes the torsional strain. The overall effect of the combined torsional and steric strains are that the boat conformation is higher in energy than the chair by 24 kJ mol-1.

Cyclohexane "Ring-flips"

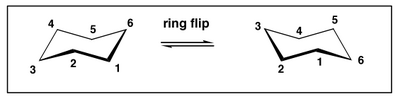

Cyclohexane, like any other molecule, is not a static object but continually moves and changes shape. Out of all the possible shapes, the chair conformations are the lowest in energy, so statistically speaking we would, if we could take a snapshot, see that conformation most often. However, there are two chair conformations that the molecule can adopt. Both have the same energy.

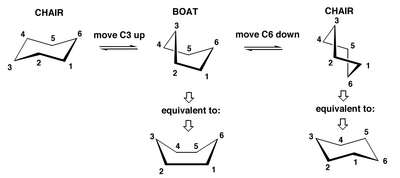

The ring does this not, in fact, by magic, but through a tortuous and very fast rearrangement through an intermediate boat conformation that can help us to visualise what is going on. Clearly there will be a barrier to the ring-flipping, in that case.

The Consequence of the Ring-Flip

...is that axial and equatorial protons interchange.

Despite there being a barrier, the ring-flipping for cyclohexane is fast. If we take an 1H NMR spectrum we see a single peak for cyclohexane, not a peak for axial and a peak for equatorial protons.

Monosubstituted Cyclohexanes

So far we've just been looking at cyclohexane itself, which is simple and symmetrical. The world is full of molecules containing substituted cyclohexanes, so we ought to examine whether all the things we just saw apply to these systems too. The short story is Yes - substituted cyclohexanes generally behave the same way, in that we see a general preference for chairs over boats, and the molecule is dynamically moving. But introducing groups on the ring has an interesting and very important effect on the ring-flip.

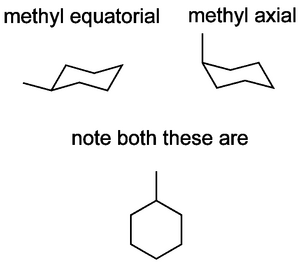

Let's look at methylcyclohexane. The chair form is preferred, as before. But the two chair conformations don't look the same, as they did for cyclohexane itself. In one case the methyl is axial, and in the other case it's equatorial.

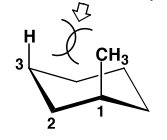

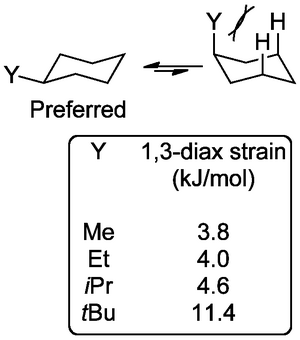

When the methyl is axial, there is a new steric strain, called a 1,3-diaxial clash, costing (in this case) 3.8 kJ mol-1.

So while we see both conformations, the lowest energy conformation with the methyl equatorial is preferred. Logically this strain gets worse if the substituent is something larger than methyl.

By the time the substituent is tert-butyl the difference in chair conformation energies is so great that we essentially never see the conformation where the tert-butyl is axial. The substituent essentially shuts down the usual ring-flip and we see the ring locked in one conformation. Here's the axial:

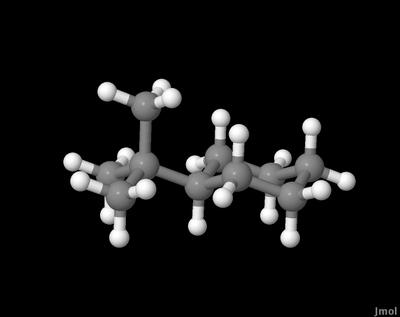

...and here's the equatorial:

This restriction on movement, imposed by substituents, is extremely important in many areas of chemistry and biochemistry.

The Licence for This Page

Is CC-BY-3.0 meaning you can use whatever you want, provided you cite me.