BISC209/S12: Lab6

Lab 6: Identification of Bacteria by 16s rRNA gene sequencing & Continue Characterization of Bacterial Isolates from the Soil Community

The isolate amplicons (PCR products) were (or will be) submitted to GeneWiz, a DNA sequencing facility in Cambridge, MA. The data should be back well before we have scheduled time for analyzing it.

Continue Antibiotic Production test started last week

Week 2

Need fresh control cultures of Eschericia coli (Gram negative), Staphylococcus epidermidis (Gram positive) and Micrococcus luteus (Gram positive) grown in nutrient broth to the same turbidity standard used last week for isolate cultures. Use the MacFarland Standard to make sure that these cultures are of the same turbidity as your isolates were when you applied them to the NA plates last week. If not, dilute a little of the stock control cultures (in separate sterile tubes)to appropriate turbidity with nutrient broth.

PROTOCOL

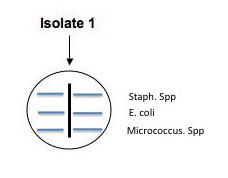

Use the cultures of your isolates set up last week on NA.

Use a sterile swab to aseptically apply parallel lines of inoculation of each of the control broth cultures of : E. coli, Micrococcus, and S. epidermidis as shown in the illustration below. Use a different sterile swab for each culture. These parallel inoculation lines should be made perpendicular to the putative antibiotic producer's (your isolate's) colony growth. (See the illustration.) Be careful not to touch the putative antibiotic producer's growth with the control cultures, but come as close as you can. Make a template in your lab notebook and label the plate to indicate where each control culture is streaked. Incubate these culture plates at RT in a place that where your instructor can monitor their development. One person/lab should also set up viability controls by swabbing each the three broth cultures onto separate areas of another NA plate. If you see growth of each of the controls next week, we will be sure that any inhibition of growth is due to sensitivity to a diffused antibiotic rather than lack of growth occurring because one or more of the control broth cultures you used today lacked enough viable cells to form colonies on your test plate.

Physical & Functional Capabilities of Your Cultured Isolates:

MOTILITY & ABILITY TO REDUCE NITRATE TO NITRITE (reverse part of the nitrogen cycle):

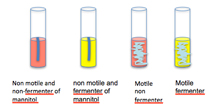

Every isolate should be inoculated into a soft agar deep of mannitol nitrate motility medium (MNM): 1% casein peptone; 0.75% mannitol; 0.1% potassium nitrate; 0.004% phenol red; 0.35% agar. "Soft" agar contains much less solidifying agent (agar) than most solid media (0.35% rather than the usual 1.5%). The growth pattern in this semi-solid NA medium gives information about motility. The soft agar MNM gives additional information about other metabolic capabilities such as the ability to use mannitol as a carbon source and the ability of a microorganism to reduce nitrate to nitrite.

A full description of these tests can be found in the protocols section: Motility Tests.

If either of your motility test are positive when we analyze the results, you could try to confirm motility with a hanging drop technique or by trying a flagella stain.

PROTOCOL:

Inoculating a soft agar deep involves a technique you have not yet practiced. You will use an inoculating needle: the wire extending from the handle of the needle will not have a loop on the end.

1) You will need a tube of soft MNM medium for each of your isolates. Each class needs to add 2 extra tubes of soft agar medium to inoculate one with E. coli, an organism that is motile, which will serve as a positive motility control and the other with Staphylococcus epidermidis, an organism that is non-motile, to serve as our negative motility control.

2). Flame sterilize an inoculating needle, cool it for a few seconds, and pick up a barely visible amount of colony growth on the tip of the needle.

3) Stab the needle with the inoculum deeply into the center of the soft agar tube, stopping just before the bottom of the tube or, if you are running out of needle, stab it until the you are almost to the end of the needle.

4) Withdraw the needle through the same inoculation channel. (This procedure is also known as "making a soft agar deep".)

5) Inoculate each of your other isolates using the same technique.

6) Make sure the class has inoculated a positive control tube of E. coliand a negative control tube of S. epidermidis.

7) Incubate all tubes for 24-72 hours. The MNM tubes should be incubated at RT.

8) After sufficient growth is observed in the MNM tube, look for a color change from red to yellow. Use of mannitol as a carbon source results in a pH change that we can see using phenol red indicator (change from red to yellow).

9) Check for motility by looking for diffuse growth radiating from the stab line of inoculation. Compare the motility of each of your isolates to that of the E. coli positive control and the Staph negative control. E. coli are a motile bacteria and all Staphyloccus species are non-motile.

9) In lab 7 we will develop the nitrate to nitrite test in the MNM tube by adding Gries reagent (2 drops of solution A, and then 2 drops of the solution B) to the surface of the medium. Nitrate non-reducers-negative organisms are unable to reduce nitrates and they yield no color after adding the reagent. Nitrate reducers-positive: The appearance of a pink or red coloration indicates that the nitrates have been reduced to nitrites.

Gries reagent consists of solutions:

Solution A

Sulfanilic Acid 0.8% (v/v) in Acetic Acid 5N

Solution B

Alpha-Naphthylamine (0.001% v/v)

in Acetic Acid 5N

Control Organisms:

| Organism | ATCC | Motility | Mannitol as Carbon Source | Nitrate to Nitrite |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Escherichia coli | 25922 | + | + | + |

| Klebsiella pneumoniae | 13883 | - | + | + |

| Proteus mirabilis | 25933 | + | - | + |

| Acinobacter anitrartum | 17924 | - | - | - |

Microbiologists of previous generations had to do their bacterial identification exclusively from physical and metabolic tests. The tests we are performing in the course of our investigation are a tiny subset of all the morphologic, metabolic, and other tests that you could perform on your isolates to try to identify them through a battery of tests for different metabolic capabilities and characteristics. Be very glad that you are training as a microbiologist in the era of genomics!

Assessing Bacterial Morphology and Characteristic Arrangement and Cell Wall Composition by Gram Stain

Today you will make smear slides (explained here and in Protocols as Smear Slide Preparation) and perform Gram stains (found here and in protocols as Stains: Gram Stain).

Activity: Preparing a bacterial smear slide

1. Use a graphite pencil to label on the far left side of a clean, glass slide the code ID or name of three of your isolates. If you have more than 3 isolates, make two slides with no more than 3 organisms/slide.On an additional clean, glass slide, label a control slide as SE (Staphylococcus epidermidis), EC (Escherichia coli), and EC/SE mix.

2. Prepare the "control" slide first by using your loop to apply three tiny drops of deionized water to different parts of this pre-labeled slide. Flame sterilize the loop, allow it to cool for a few seconds and touch the cooled loop to a single colony of the control culture plate of S. epidermidis. Pick up a VERY, VERY TINY bit of growth from a single bacterial colony. An invisible amount of growth obtained from just touching the cooled loop to the colony will give you plenty of bacteria. If you take a glob, the bacteria will be so thick, you will not get good stain results.

3. Place the loop with the bacterial growth into the drop of water. Use a circular motion with the loop to make a smooth suspension of the bacteria in the water. Stop when you have spread out the circle of emulsified bacteria as much as possible, while making sure to leave room to make two other smears on the slide. Reflame your loop and repeat the process of inoculating theE. coli control into both the middle drop of water and the drop on the far right. Mix the middle drop of E. coli emulsion as you did for the Staph smear. Flame your loop and cool it for a few seconds. Touch your loop again to a Staphylococcus colony (just a TINY bit) and inoculate the drop of water on the far right, to mix the Staph with the E. coli in the last smear. Spread the bacteria in the mixed smear evenly.

4.Now you are ready to make smears of your isolates. Using your best aseptic technique, flame sterilize your loop. Apply a very small loopful of deionized water (bottle on your bench) to the slide and then add a tiny amount of bacteria from a fresh culture growing on solid medium of one your isolates. Create the smear as you did for the controls moving from left to right and spacing the smears so that 3 isolates can fit on one slide. Repeat for the other isolates. Broths can also be used to make a smear. In this case, be sure to mix the broth, carefully vortex or tap the bottom of the tube. Remove the culture tube top (NOT placing it on the bench) and pass the lip of the culture tube rapidly through the flame. Dip your loop into the broth culture and place a small drop of broth culture of that isolate on the appropriate place on the labeled slide. (The labeling from top to bottom should refer to isolates placed left to right.) Mix the drop with your loop to disperse the broth over an area that will not touch the next culture but is large enough to allow your slide to dry quickly.

5. Allow the smears to air dry completely! Be sure all the water on the slide has evaporated before proceeding to heat fixation!!! This drying step is crucially important. If you are impatient, you will "explode" the cells in the next step .

6. Heat fix (to kill and attach organisms to the slide) by passing the slide (smear side up) quickly through a flame 3 times. Use a clothes pin or slide holder to avoid contact with hot glass.

An example of a multiple smear labeled slide:

The Gram Stain

Background on Using Stains in Bacteriology

The first of the dyes most useful to bacteriologists was a reddish violet dye, mauvein, synthesized in England by William. H. Perkin, and patented by him in 1856. This synthetic dye and others were immediately appreciated by histologists, but were not applied to bacterial cells until Carl Weigert (a cousin of Paul Ehrlich) used methyl violet to stain cocci in preparations of diseased tissue in 1875. Subsequently, the use of various synthetic dyes for bacteriological preparations developed rapidly when they were promoted through the publications of Robert Koch and Paul Ehrlich.

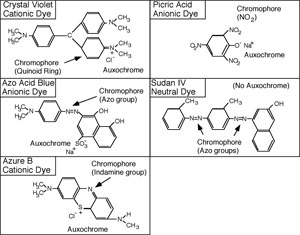

The synthetic dyes are classified as acid dyes, or basic dyes, depending on whether the molecule is a cation or an anion. The introduction of the terms acidic and basic was unfortunate because it would be more revealing to refer to them as cationic or anionic dyes. A look at the structural formula reveals the nature of the dye.

Each dye molecule has at least two functional chemical groupings. The auxochrome ionizes and gives the molecule the ability to react with the substrate, while the unsaturated chromophore absorbs specific wavelengths of light. The color of the solution obtained is that of the unabsorbed (transmitted) light. To be a dye, the molecule must have both auxochrome and chromophore groups. The auxochrome is usually an ionized carboxyl, hydroxyl, or pentavalent nitrogen group. The chromophore may have unsaturated nitrogen bonds such as azo (-N=N-) indamine (-N=), nitroso (-N=O) or nitro (O-N=O), groups; or unsaturated carbon to carbon, carbon to oxygen, or carbon to sulfur bonds, such as ethenyl (C=C), carbonyl (C=O), C=S, or the quinoid ring (= = =).

Resonance is also important to color. In crystal violet, an electron resonates between the three benzene rings. As the pH of the solution is lowered, the resonance becomes more and more restricted. When the resonance is restricted from three to only two benzene rings, the solution turns from violet to green, and then to red when resonance between the two rings ceases.

Cationic dyes will react with substrate groups that ionize to produce a negative charge, such as carboxyl, phenolic, or sulfhydryl groups. Anionic dyes will react with substrate groups which ionize to produce positive charges, such as the ammonium ion. Any substrate with such ionized groups should have an ability to combine with cationic or anionic dyes. Generally, the most important staining substrates in bacterial cells are proteins, especially the cytoplasmic proteins; however, other substances also have dye affinity. These include amino sugars, organic acids, nucleic acids, and certain polysaccharides.

Sudan III, or sudan black B, is a popular stain for fatty material. It does not have an auxochrome group, and is insoluble in water, but soluble in fatty material. When a solution of sudan black B in ethylene glycol is placed over bacterial cells, the fatty material will dissolve some of the dye and thus take on the color of the sudan black. The staining effect is purely a solubility phenomenon, and not a chemical reaction, or physical adsorption.

There are many stains that can reveal the morphology of the cell, and some simple stains, such as methylene blue, are quite good for viewing bacteria. The Gram stain is especially useful because it not only reveals bacterial morphology, but also is a differential stain. A differential stain differentiates organisms. (A differential stain shows a visible difference between different groups of organisms based on some characteristic they do not share, even though the procedure to stain the different looking organisms is the same). The Gram stain relies on cell wall differences between groups of bacteria.

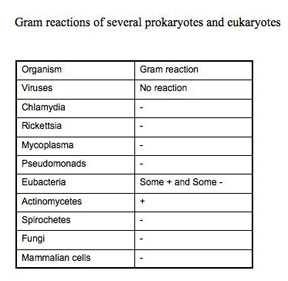

The Gram staining procedure as it is done today, involves: a) primary staining of all cells with crystal violet, b) precipitating the primary stain dye within the cells with iodine (a mordant), c) removing the dye-iodine precipitate from some cells (the Gram-negative) with a decolorizer such as 95% ethanol, acetone, or n-propyl alcohol, and d) counter-staining of the decolorized cells with safranin. Organisms that retain the crystal violet primary dye are termed Gram-positive, while those which lose the primary stain and show the red safranin counter-stain are termed Gram-negative. This differentiation is not absolute, because it is based on the differences in the rate at which the primary dye is lost from the cells. If you over decolorize for too long or with too harsh a decolorizer, Gram-positive organisms will appear Gram-negative. Truly Gram-positive cells, such as Bacillus subtilis or Staphylococcus aureus, will not retain the primary dye if the iodine step is omitted. Criteria for a true Gram-positive state include the requirement of iodine following the crystal violet.

Since the term Gram positive or Gram negative actually refers to a type of cell wall, not all organisms that retain the primary dye of the Gram procedure are really Gram-positive, because they lack that particular cell wall composition. For example, Mycobacterium species have a different type of cell wall but they will take up and retain crystal violet if you use heat. In this case, the crystal violet will be resistant to harsh decolorization and be retained. However, a Mycobacterium type cell wall does not require the use of a mordant, like iodine, to precipitate the stain. True Gram-positive organisms do not retain the primary crystal violet without precipitation by a mordant. Using crystal violet with heat, harsh decolorization, and no mordant describes an acid-fast stain rather than a Gram stain. Mycobacteria have an acid-fast type cell wall; they are neither Gram-positive or Gram-negative, despite the fact that they will appear purple if you do a Gram-stain on them.

Activity: Preparing a Gram Stain

The Gram stain is a standard DIFFERENTIAL staining technique useful for the identification of culturable bacterial organisms and you will perform it now. Remember that a differential stain is one in which different bacteria are subjected to the same stain procedure but they respond differently and show a visible differentiation. In this case, that visible difference is pink vs purple color and it is based on cell wall composition differences.

Use the smear slides you have prepared of your isolates and the controls and follow the Gram Stain Protocol found below. This protocol can also be found in BISC209/S12: Stains in the protocol section of this wiki.

Gram Stain Procedure:

Here is a link to a good video on Gram staining [1]

To Gram stain the previously prepared heat fixed, bacterial smear slides, perform the staining protocol from start to finish on one slide at a time. You must be careful to apply the staining reagents liberally so all the smears are evenly and completely covered and you must be sure to expose each smear to each reagent for the same amount of time.

1. Place a heat-fixed bacterial smear slide on the staining tray. It is important that the slide is level during staining; therefore, you should use paper towels under the tray to level the slide. If you do this, it is much easier to ensure that your smears will be covered evenly with each reagent with as little waste of the dye as possible (a crucial aspect of proper staining results).

2. Dispense just enough Crystal Violet solution (0.5% crystal violet, 12% ethanol, 0.1% phenol) to completely cover each smear and stain for 1 minute. (Crystal violet is the primary stain.)

3. Rinse the slide by lifting the slide at a 45 degree angle (using gloves or a clothes pin or slide holder) and use a squirt bottle to direct a very gentle stream of water slightly above the top smear. Rinse until the waste water coming off at the bottom is relatively clear. Drain off excess water by touching the edge of the slide to a paper towel.

4. Dispense just enough Gram's Iodine (mordant) to completely cover each smear. Let stand for 1 minute. Rinse thoroughly with a gentle stream of water as in Step 1.

5. Place the slide flat on the staining tray and dispense just enough decolorizing Reagent (80% isopropyl alcohol, 20% acetone) to completely cover each smear. Let stand for exactly 10 seconds and IMMEDIATELY rinse in a very gentle stream of water that is directed above the top smear as in step 3. This step is tricky as it is easy to over- or under-decolorize. .

6. Place the slide flat on the staining tray and dispense just enough Counterstain (0.6% safranin in 20% ethanol) to cover each smear. Let stand for 1 minute; rinse with water as in step 3.

7. Blot dry using the bibulous paper package found in your orange drawer. Do not tear out the pages, just insert your slide and pat it dry.

8. Clean up your area; rinse your staining tray in the sink and leave it to drain upside down on paper towels.

Use of the Compound Light Microscope

Activity: View your stained bacteria.

Refer to the directions for using your compound brightfield microscope BISC209/S12:_Microscopy found in the Protocols section. Today you will use only the 10x and 100x objectives. Remember also to read and follow the directions for care of this precision instrument (particularly on how to avoid getting immersion oil on any objective other than the 100x oil immersion lens). Be aware that there would be no field of microbiology if there weren't good, functioning microscopes to view this unseen world.

Gram Reaction Confirmation by use of Selective/Differential Media

Activity: Performing a Spot Inoculation Technique on Selective/Differential Media to Assess Cell Wall Composition (Confirm Gram stain)

You will inoculate each of your isolates onto both eosin methylene blue (EMB) and phenylethyl alcohol (PEA) solid media. Consult Culture Media: Use of Selective & Differential media to confirm Gram stain to learn how these media are able to select for either Gram positive or Gram negative bacteria and, in the case of EMB, to differentiate lactose fermenting bacteria from non-lactose fermenters. You should test all your isolates on both media to confirm your Gram stain results. You will be expected to know how these media select and differentiate for cell wall characteristics and/or metabolic differences.

PROTOCOL:

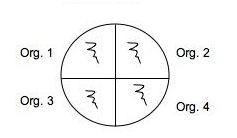

Use a marker to divide the bottom of 2 plates of each medium into 4 sections and organize a labeling system in your lab notebook and on the plate so you can easily identify where you placed each of your soil isolates: 2 isolates and a positive and negative control on one plate of each medium and another plate of each medium can be used for the rest of your isolates with or without controls. (Use E. coli and Staph as controls.) You will spot inoculate the middle of each quadrant by taking a tiny amount of growth and inoculating a single thin zig-zag line in the center of a section. Incubate your plates at room temp for several days until you are sure that any inhibition of growth is from selection and not from slow growing bacteria. Put the plates in the refrigerator before they get overgrown. You can analyze them in Lab 7. See the illustration below of how to inoculate a plate with 4 different cultures.

Fig: 6-1. Testing of multiple isolates in one plate can be accomplished by dividing a plate into 4 (OR MORE) sections. Be sure the inoculum is placed in the center of each section and that you check the plate for growth regularly.

CLEAN UP

1. All culture plates that you are finished with should be discarded in the big orange autoclave bag near the sink next to the instructor table. Ask your instructor whether or not to save stock cultures and plates with organisms that are provided.

2. Culture plates, stocks, etc. that you are not finished with should be labeled on a piece of your your team color tape. Place the labeled cultures in your lab section's designated area in the incubator, the walk-in cold room, or at room temp. in a labeled rack. If you have a stack of plates, wrap a piece of your team color tape around the whole stack.

3. Remove tape from all liquid cultures in glass tubes. Then place the glass tubes with caps in racks by the sink near the instructor's table. Do not discard the contents of the tubes.

4. Glass slides or disposable glass tubes can be discarded in the glass disposal box.

5. Make sure all contaminated, plastic, disposable, serologic pipets and used contaminated micropipet tips are in the small orange autoclave bag sitting in the plastic container on your bench.

6. If you used the microscope, clean the lenses of the microscope with lens paper, being very careful NOT to get oil residue on any of the objectives other than the oil immersion 100x objective. Move the lowest power objective into the locked viewing position, turn off the light source, wind the power cord, and cover the microscope with its dust cover before replacing the microscope in the cabinet.

7. If you used it, rinse your staining tray and leave it upside down on paper towels next to your sink.

8. Turn off the gas and remove the tube from the nozzle. Place your bunsen burner and tube in your large drawer.

9. Place all your equipment (loop, striker, sharpie, etc) including your microfuge rack, your micropipets and your micropipet tips in your small or large drawer.

10. Move your notebook and lab manual so that you can disinfect your bench thoroughly.

11. Take off your lab coat and store it in the blue cabinet with your microscope.

12. Wash your hands.

Assignment

One to 3 days(depending on how fast your organisms grow) prior to Lab 7, please prepare a fresh both culture of each isolate into sterile nutrient broth.

On the same day you make the broths, subculture by isolation streaking EACH of your isolates onto nutrient agar. In Lab 7 these cultures will be used by your team for the interaction assay.

Graded Assignment:

Prepare a discussion that explains use and the theory behind the following tools that we used to identify our bacteria by 16s rRNA gene sequencing:

Polymerase chain amplification of the 16s rRNA gene: including visualization of pcr products

DNA sequencing by the fluorescent-labeled ddNPTs chain-termination (Sanger) method.(Do not describe the radioactive labeling method!!!)

Directions for this assignment found at: Lab 6 Assignment: Assignment: Theory Summary