Péclet number (Pe) - Nishanth Saldanha: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

|||

| Line 75: | Line 75: | ||

== Applications to Microfluidics == | == Applications to Microfluidics == | ||

Low length and velocity scales in microfluidic setups- > Low Reynolds number. This also implies lower convective forces when compared to larger devices. As such, Pe in a microfluidic device is usually lower than 1 and as such, implying that these regimes are diffusion dominant[Squires and Quake] | |||

This has an effect in making turbulence non existent in microfluidic devices. Turbulence in macro-world often leads to faster mixing -> Diffusion induced mixing is slower than covective mixing ->Slow as in different time scales (order of minutes) [Squires and Quake]. | |||

Thus, low Pe systems (Pe<1), have trouble getting good mixing -> If no mixing is desired, this can be optimal. However, in reaction systems, where mixing is necessary for reactions, Low Pe can be a hindrance [Squres and Quake]. While length of channels can be increased to increase Pe, this may not be optimal in all cases. | |||

The molecules dissolved in the liquid also have an effect on Pe. Larger species (proteins for example) have lower diffusion constants than salt ions (by three orders of magnitude in um^2/s). These differences in diffusivities can be taken advantage of in separation systems, as shown by the H-filter by Squires and Quake. Essentially, species with lower diffusivities will not travel as far as species with higher diffusivities. Thus, separation can be achieved in a 'H' shaped channel, where a mixture will enter on the ends of the 'H' and a separation will occur such that the low mass specie will exit the bottom of the same side, while the lighter specie will traverse the middle section of the H onto the other side. Such a device can also help with buffer exchange or to separate non motile sperm from motile sperm, for example | |||

T-sensors are another class of devices that take advantage of the low Pe regimes. In these systems, two pure solutions enter on the top two ends of a 'T' junction, and then mix on the middle section of the 'T'. Low Pe, means that the mixing can be seen as function of the position on the middle section ->As one moves further down, more diffusion occurs. This also allows one to clearly view the differential mixing that occurs, where the pure species are also visible. This can be helpful in many analytical tests. | |||

Both devices work in intermediate Pe range (Pe around 1), but differences in diffusivities among species is critical. | |||

At Pe>>1, mixing can occur, either due to convectively-stirred mixing or through Taylor dispersion mediated mixing. | |||

== References == | == References == | ||

Revision as of 23:06, 22 March 2017

Definition

The Péclet number (Pe) is a dimensionless number that represents the ratio of the convection rate over the diffusion rate in the a convection-diffusion transport system. [1][2]

[math]\displaystyle{ Pe = \frac{(Convection \, rate)}{(Diffusion \, rate)} = \frac {UL}{D} }[/math]

U represents linear flow in a control volume, L represents the length scale of the flow and D is the diffusion constant. This number can also be represented as a ratio of diffusive to convective time scales.

[math]\displaystyle{ Pe = \frac{(Diffusion \, timescale)}{(Convection \, timescale)} }[/math]

In diffusion dominated regimes, the Peclet number is less than 1. Such is the case with microfluidic systems, where turbulence is low. In convection dominated systems, this number is greater than one.

Derivation [3]

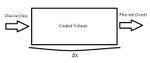

For a one dimensional system as described in Figure 1, with a specie concentration, [math]\displaystyle{ C }[/math] following relations can be made to relate flux in, [math]\displaystyle{ J_{in} }[/math] , flux out,[math]\displaystyle{ J_{out} }[/math] and control volume [math]\displaystyle{ V }[/math]. From this system, the Péclet number can be derived.

[math]\displaystyle{ V\frac{dC}{dt} = A\cdot J_{in} - A\cdot J_{out} }[/math]

This mass balance can be used to describe the flux into and out of the system. Flux is mass flow rate per unit area. Assuming inlet and outlet areas are constant, the mass balance can be simplified.

[math]\displaystyle{ \frac{dC}{dt} = \frac{A}{V}\cdot (J_{in} - J_{out}) }[/math]

If there are gradients in the system, the flux out of the system can be described as follows.

[math]\displaystyle{ J_{out} = \frac{\partial J}{\partial x}\cdot (\Delta x)+J_{in} }[/math]

Thus, the mass balance can be simplified as shown below.

[math]\displaystyle{ \frac{dC}{dt} = \frac{A}{V}\cdot \frac{\partial J}{\partial x}\cdot (\Delta x) }[/math]

Due to how the system is defined, [math]\displaystyle{ \frac{A}{V} = \frac{1}{\Delta x} }[/math]. Thus,

[math]\displaystyle{ \frac{dC}{dt} = \frac{\partial J}{\partial x}\rightarrow \frac{\partial C}{\partial t} =\triangledown J }[/math]

This equation is also described in three dimensions.

The assumption of negligible sources and sinks are made, so as to focus the system on diffusion and convection. Thus,

[math]\displaystyle{ J = J_{convection}+J_{diffusion} }[/math]

Mass flow rate, [math]\displaystyle{ Q }[/math], can be defined as [math]\displaystyle{ Q = C \Delta x\cdot A }[/math]. Since the convection is the prime source of this mass flow rate in this system, convective flux, [math]\displaystyle{ J_{convection} }[/math] is defined as such.

[math]\displaystyle{ J_{convection} = \frac{Q}{\Delta t\cdot A} = \frac{C \Delta x }{\Delta t} \rightarrow \frac{\partial x}{\partial t}C }[/math]

Diffusion equation can be derived from first Fick's law as shown below. [math]\displaystyle{ D }[/math] is the Diffusivity constant.

[math]\displaystyle{ J_{diffusion} = -D \frac{\partial C }{\partial x} }[/math]

Diffusive flux and Convective flux can be combined into the overall mass balance.

[math]\displaystyle{ \frac{\partial C}{\partial t} = -\frac{\partial \left [ J_{convection}+J_{diffusion} \right ]}{\partial x} = -\frac{\partial \left [ \frac{\partial x}{\partial t}C + -D \frac{\partial C }{\partial x} \right ]}{\partial x} }[/math]

Because the relation below can be applied, where [math]\displaystyle{ u }[/math] equals velocity of a particle, the mass balance can be simplified and described in multiple dimensions

[math]\displaystyle{ \frac{\partial x}{\partial t} = u }[/math]

[math]\displaystyle{ \frac{\partial C}{\partial t} = D\frac{\partial^{2} C}{\partial x^{2}} - u \frac{\partial C}{\partial x}\rightarrow \frac{\partial C}{\partial t} + u \frac{\partial C}{\partial x}= D\frac{\partial^{2} C}{\partial x^{2}} \rightarrow \frac{\partial C}{\partial t} + u \triangledown C= D \triangledown^{2} C }[/math]

Dimensionless numbers, as shown below can be used to restate the mass balance. [math]\displaystyle{ U }[/math] equals the convective linear flow rate.

[math]\displaystyle{ C^{*} = \frac {C}{C_{max}}; U^{*} = \frac{u}{U}; t^{*} = \frac {t}{t_{0}} }[/math]

When these numbers are applied, the balance is described as shown.

[math]\displaystyle{ \frac{C}{t_{0}}\frac{\partial C^{*}}{\partial t} + \frac{UC}{L}u^{*} \frac{\partial C}{\partial x}= \frac{DC}{L^{2}}\frac{\partial^{2} C}{\partial x^{2}} }[/math]

[math]\displaystyle{ \frac{L^{2}}{D\cdot t_{0}}\frac{\partial C^{*}}{\partial t} + \frac{UL}{D}u^{*} \frac{\partial C}{\partial x}= \frac{\partial^{2} C}{\partial x^{2}} }[/math]

The first term in the above balance is referred to as the unsteady term. In time invariant flows, this term equals zero. The ratio between the remaining two terms (i.e. the diffusive and convective terms), equals the Peclet number, as described below.

[math]\displaystyle{ Pe = \frac {UL}{D} }[/math]

Applications to Microfluidics

Low length and velocity scales in microfluidic setups- > Low Reynolds number. This also implies lower convective forces when compared to larger devices. As such, Pe in a microfluidic device is usually lower than 1 and as such, implying that these regimes are diffusion dominant[Squires and Quake]

This has an effect in making turbulence non existent in microfluidic devices. Turbulence in macro-world often leads to faster mixing -> Diffusion induced mixing is slower than covective mixing ->Slow as in different time scales (order of minutes) [Squires and Quake].

Thus, low Pe systems (Pe<1), have trouble getting good mixing -> If no mixing is desired, this can be optimal. However, in reaction systems, where mixing is necessary for reactions, Low Pe can be a hindrance [Squres and Quake]. While length of channels can be increased to increase Pe, this may not be optimal in all cases.

The molecules dissolved in the liquid also have an effect on Pe. Larger species (proteins for example) have lower diffusion constants than salt ions (by three orders of magnitude in um^2/s). These differences in diffusivities can be taken advantage of in separation systems, as shown by the H-filter by Squires and Quake. Essentially, species with lower diffusivities will not travel as far as species with higher diffusivities. Thus, separation can be achieved in a 'H' shaped channel, where a mixture will enter on the ends of the 'H' and a separation will occur such that the low mass specie will exit the bottom of the same side, while the lighter specie will traverse the middle section of the H onto the other side. Such a device can also help with buffer exchange or to separate non motile sperm from motile sperm, for example

T-sensors are another class of devices that take advantage of the low Pe regimes. In these systems, two pure solutions enter on the top two ends of a 'T' junction, and then mix on the middle section of the 'T'. Low Pe, means that the mixing can be seen as function of the position on the middle section ->As one moves further down, more diffusion occurs. This also allows one to clearly view the differential mixing that occurs, where the pure species are also visible. This can be helpful in many analytical tests.

Both devices work in intermediate Pe range (Pe around 1), but differences in diffusivities among species is critical.

At Pe>>1, mixing can occur, either due to convectively-stirred mixing or through Taylor dispersion mediated mixing.

References

[[1]] "Advection and diffusion of an instantaneous release". Heidi Nepf. 1.061 Transport Processes in the Environment. Fall 2008. Massachusetts Institute of Technology: MIT OpenCourseWare, License: Creative Commons BY-NC-SA.

[[2]] Incropera, F., DeWitt, D., Bergman, T., Lavine, A. Fundamentals of Heat and Mass Transfer”; Wiley: New York. 2011

[[3]] "Derivation of basic transport equation". Ali Ertürk. Lagoon Ecosystem Modelling (ECOPATH/ECOSIM): From Hydrodynamics to Fisheries. June 21- 23, 2011, University of Klaipeda and Leibniz Institute for Baltic Sea Research Warnemünde