Thayer Lab

Mathew J. Thayer, Ph.D.

Associate Professor

Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology

Oregon Health & Science University

3181 SW Sam Jackson Park Road

Portland OR 97239

(503)494-2447

thayerm@ohsu.edu

Education:

California State University, Chico. BA: Microbiology and Chemistry (1982)

University of Southern California. PhD: Microbiology (1988)

RESEARCH INTERESTS

My laboratory uses somatic cell and molecular genetic approaches to identify and characterize genetic alterations found in tumor cells that induce abnormal cellular phenotypes. By utilizing this approach, my lab has identified a previously unknown chromosomal abnormality that is associated with certain chromosomal rearrangements. This chromosomal phenotype is characterized by a delay in mitotic chromosome condensation, a delay in the chromosome replication timing, and significant chromosomal instability. Chromosomes with this phenotype are common in tumor derived cell lines and in primary tumors. Furthermore, we have found that exposing cells to ionizing radiation generates chromosomes with this phenotype. Our findings support a model in which the chromosomal instability found in tumor cells, and in cells exposed to ionizing radiation, stems from a defect in the replication timing of certain chromosomal rearrangements. Recently, we developed a chromosome engineering strategy that allows us to generate chromosomes with this delayed replication and condensation phenotype in an efficient and reproducible manner. Our findings indicate that ~5% of all random chromosome translocations display this abnormal phenotype. In addition, on certain balanced translocations only one of the derivative chromosomes displays the phenotype, indicating that a cis-acting mechanism is responsible for this abnormal chromosomal phenotype. We are currently using ‘chromosome engineering’ strategies, combined with somatic cell and molecular genetic approaches, to generate and characterize chromosomes with this delayed replication and condensation phenotype. The long-term goal of these studies is to define the molecular mechanisms responsible for chromosomal instability, one of the most common types of genetic instabilities found in cancer cells.

Chromosomes with DRT/DMC

Cancer cells differ from their normal cellular counterparts in many important characteristics, including growth factor independence, resistance to apoptotic signals, loss of differentiation, and decreased drug sensitivity. Not surprisingly, genetic alterations occur in most, if not all cancer cells, and are thought to lie at the heart of these phenotypic alterations. The genetic changes found in cancer cells are typically of two types: dominant, thought to occur in proto-oncogenes; and recessive, thought to occur in tumor suppressor genes. The dominant type of alteration typically results in a gain of function, and the recessive type of alteration typically results in loss of function. Furthermore, it has been argued that an underlying genomic instability is present in cancer cells and is required for the generation of the multiple mutations that are thought to underlie cancer. In support of this hypothesis, molecular analysis of individual tumors often identifies multiple genetic changes, including chromosomal translocations, deletions, insertions, gene amplifications, as well as point mutations. It has been estimated that every colorectal carcinoma cell contains approximately 11,000 distinct genetic alterations, present in both coding and non-coding DNA sequences. More recently, it has been shown that breast and colorectal cancers contain on average 90 mutant protein-coding genes. Determining the mechanisms responsible for the generation of these large numbers of mutations is an important goal of current cancer research. Chromosome rearrangements represent a common type of genetic alteration, and are found in nearly every type of cancer (Mitelman et al., 2004). The presence of recurring chromosome abnormalities in specific cancers occurs with remarkable specificity. Recent surveys have identified more than 600 balanced and 1,500 unbalanced recurrent chromosomal aberrations among different neoplastic disorders (Mitelman, 2000; Mitelman et al., 1998; Mitelman et al., 2006). These recurrent genetic alterations have been the focus of intensive molecular analysis for many years, with over 300 genes being implicated in various neoplasia-associated chromosomal rearrangements (Mitelman et al., 2004). Furthermore, these recurrent structural alterations can assist in the diagnosis and sub-classification of a malignant disease and in the selection of the appropriate treatment.

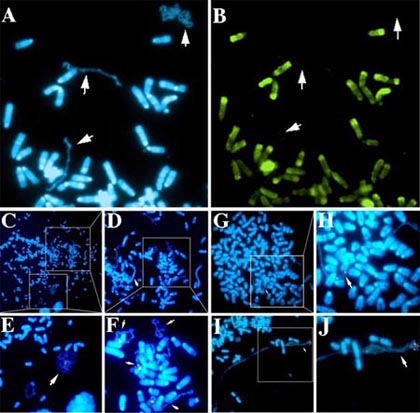

In addition to these recurrent chromosomal alterations, most solid tumors also contain many non-recurrent chromosomal changes, with >100,000 independent alterations having been documented (Mitelman et al., 2006). These non-recurrent changes are seen as simple balanced or unbalanced translocations, intra-chromosomal rearrangements (deletions, inversion, or duplications), or as marker chromosomes and gene amplifications. Unfortunately, the mechanisms responsible for the generation of these numerous chromosomal alterations and the molecular and phenotypic changes associated with the majority of these alterations remain undefined. My lab has characterized an abnormal chromosomal phenotype that is associated with certain tumor-derived and radiation induced chromosome alterations. These chromosomes display a significant delay in mitotic chromosome condensation (DMC), associated with a delay in the mitosis-specific phosphorylation of histone H3, and a 2-3 hour delay in the replication timing (DRT) of the entire chromosome. In addition, chromosomes with DRT/DMC participate in frequent secondary translocations and rearrangements, indicating that cells containing these chromosomes display CIN. The results that we have obtained during the characterization of chromosomes with DRT/DMC support a model in which the genetic instability found in tumor cells and in cells exposed to ionizing radiation stems from a defect in the replication timing of certain chromosomal rearrangements, and that this abnormal replication is regulated by a cis-acting mechanism. Individual cells can contain multiple chromosomes with the DMC phenotype, and the DMC chromosomes within a given cell can display a wide range in the extent of mitotic chromosome condensation (Fig. 1C-F). Furthermore, chromosomes with the more extreme under-condensed appearance lack the mitosis-specific phosphorylation of histone H3 on serine 10 (Fig. 1A and B) usually initiated in late G2 and completed just prior to nuclear envelope breakdown and the formation of prophase chromosomes. These observations suggest that the more extreme under-condensed chromosomes retain an “interphase state” of condensation in cells that contain fully phosphorylated and condensed metaphase chromosomes.

Engineering DRT/DMC

We have developed a chromosome engineering system that allows us to: 1) target the genome in a random fashion, 2) create reciprocal chromosome translocations at defined locations, 3) generate the same translocations in multiple independent events using two distinct mechanisms, and 4) characterize the chromosomes both before and after the translocation events. The chromosome engineering strategy that we are employing is based on the Cre/loxP site-specific recombinase system to generate inter-chromosomal translocations. Because the Cre/loxP system is relatively inefficient at generating inter-chromosomal translocations (<1 x 10-3), we are using reconstitution of a selectable marker to isolate the cells that undergo Cre-mediated recombination. A schematic representation of this strategy is shown in Fig. 2.