Microfluidic Sensing- Diana Barr

Introduction: Microfluidic Sensing

Sensors encompass a variety of technologies that, in response to changes that occur, produce signals sent to a transducer to convey information about a system. Sensors typically consist of three major components which include electrical circuits, conversion element, and a sensing element. Microfluidics has allowed for microfluidic sensing to make an impact in these technologies with a range of applications in biotechnology, medicine, chemistry, and engineering.[1] With optical, electro-based, and several other sensing technologies combined with microfluidics, sensor development and integration in microfluidic devices has gained attention in the field of microfluidic research. It should be emphasized, nevertheless, that microfluidic sensing technologies are quickly developing to match commercial requirements.[2]

Optical Sensing

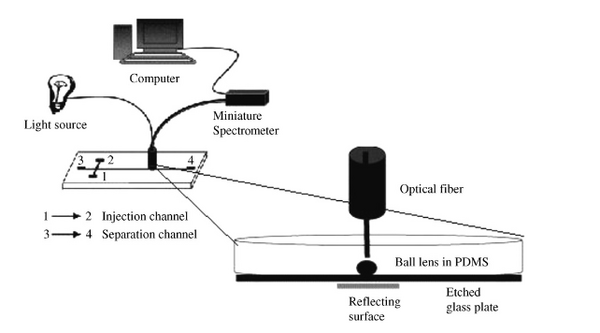

Optical Sensing due to its selectivity and sensitivity is typically regarded as one of the more preferred microfluidic detection techniques. Microfluidic optical detection techniques rely on methods that measure light characteristics including fluorescence, absorbance, luminescence, and surface plasmons. The majority of optical sensing techniques include integrated electronic processing, including fiber optics, microprocessors, and resonance filtering.[3] An example of a fiber optics microfluidic detection device can be seen in Figure 1.

As a result of its excellent precision and mobility, fluorescence detection is the most preferred and used optical sensing technique in microsystems. The spectroscopic technique known as LIF (laser induced fluorescence) is most frequently utilized in microfluidics because it is simple to adapt to small device size. As per Beer's Law, the sensitivity of absorbance sensing is constrained, but fluorescence detection has a considerably wider range of sensitivity. Beer's Law relates the absorption of light to the material through it travels. The absorption of light will not be substantial for very thin samples, as in some microfluidic systems, which will restrict the detection. The attenuation of light does not, however, determine the sensitivity of detection using sensor techniques like LIF.[4]

Electro Based Sensing

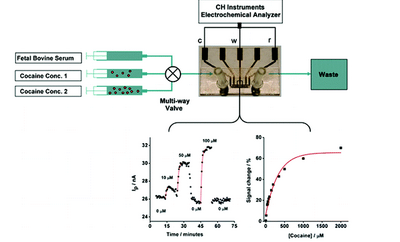

Electro Chemical Sensing Electrochemical sensing is primarily based on changes in the electrical properties of analyte species that undergo redox reactions. The electroactive species are then detected using these measurements. The oxidation or reduction of electroactive species results in an induced electrical current, which is the foundation of electrochemical sensing. Via the electrode's current vs. time graphs, detection may be observed in real time. Several electrochemical techniques are used for various purposes, such as potentiometric detection and amperometric detection. [3] An example of an electrochemical sensor can be seen in Figure 2, depicting a sensing setup for cocaine detection as well as detection graphs.

There are three subcategories of electrochemical detection techniques: conductometic, potentiometric, and amperometric. [2] Electrical sensing for microfluidics has recently undergone innovation in addition to electrochemically based sensing. Namely, capacitive, conductive, and resistive sensing have all been successfully included into microfluidics. [5]

Mass Spectrometry Sensing

Mass Spectrometry Sensing is being compelled with microfluidic devices for highly selective and sensitive sensing applications. Microfluidic devices are forcing Mass Spec Sensing for very sensitive and selective sensing applications. Mass spectrometry is most frequently employed for protein separation and identifying protein fragmentation patterns since it has the ability to detect ions' trajectories in electric or magnetic fields. Although mass spectrometry sensing in microfluidics is not yet commonly employed, much baseline research is being done. Microfluidic systems can be coupled to provide high throughput processing and multiplexing capabilities. [3]

Nanomaterial Sensing

Combined with microfluidics, Nanomaterial Based Sensing paves a way to overcome some immediate challenges like precise bio-detection and ultralow velocity monitoring in the sensing area. The attractive properties of nanomaterials—which differ from those of materials at the macroscopic level and make nanomaterials highly sensitive to changes in surface chemistry—include high detection sensitivity, good compatibility with planar nanofabrication processes, high surface to volume ratios, and excellent scalability. As a result, nano-sensors can achieve extremely low detection limits (LOD).[6]

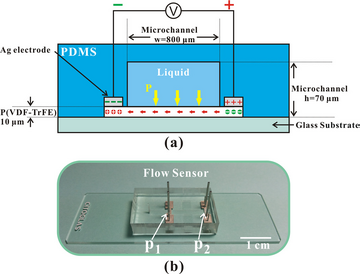

Microfluidic sensors based on nanomaterials can be used for environmental sensing to track and analyze changes in ambient conditions including temperature, pressure, and chemical elements. Microfluidic sensors based on nanomaterials may be used to quantify biomolecules as well as monitor flow velocities. An example of a microfluidic flow sensor is depicted in Figure 3. While the applications for bio-sensing, environmental sensing, chemical sensing, and other fields look promise for the nanomaterial-based microfluidic sensors due to their outstanding spatial resolution and sensitivity. Due to the presence of ion screening, the majority of these sensors are only able to be employed in solutions with modest ionic strengths.[7]

Biosensing

A Biosenser is a type of analytical tool used to analyze analytes in a sample by combining a biologically sensitive recognition element with a physicochemical detector. [8] New prospects for biosensing applications, including mobility, real-time detection, enhanced sensitivity, and selectivity, are made possible by the merging of microfluidic device and biosensor technology. [9] For use in biosensor applications, several microfluidic devices have been created. The three main types of microfluidic biosensors are enzyme-based, DNA-based, and immuno-based.

Complementary sequences of the target nucleic acid are typically immobilized in the microfluidic device using DNA-based microfluidic biosensors. The detection procedure can then be carried out in a microfluidic device by introducing samples containing the target nucleic acid into the microfluidic channel. The target nucleic acid in the sample and the base pair of the hybridization probes are both necessary for recognition. The target DNA in the sample may be examined using physicochemical signals produced by the base pairing process.

Proteins called enzymes catalyze chemical processes. Because of their distinctive binding capacities and catalytic activity, enzymes are a type of prominent bioreceptor utilized in microfluidic biosensors. In an enzyme-based microfluidic biosensor, the enzymes are generally mounted onto an appropriate transducer in a microfluidic device that generates a particular signal (optical signal, electrochemical, colorimetric, etc.) upon interaction with a particular analyte in a microfluidic channel. These signals might be used to measure several key bodily variables, like blood sugar and cholesterol, which have been linked to a number of human disorders.

The immunochemical interactions between antigen and antibody constitute the foundation of microfluidic immunosensors. Antibody typically serves as a recognition element by coming into physical contact with a transducer surface to identify the antigen in the sample. The most popular technique of detection is the enzyme-linked immunosorbent test (ELISA). Also, by observing changes in current, resistance, refractive index, etc., some microfluidic immunosensors may identify the creation of immunocomplexes.

Sweat Sensors

Microfluidic biosensors have a specialized subset called Microfluidic Sweat Sensors. Wearable microfluidic devices called microfluidic biosensors interact with the skin to collect and examine a wide range of various biomarkers. Sweat is carefully measured, tracked, and analyzed by microfluidic sensors. The sensor typically comprises of an adhesive-coated flexible yet robust "lab on a chip"-style gadget. Wearable sensors are a relatively new idea made possible by recent technological developments. Despite these recent developments, there are still many questions about microfluidic sweat sensors. This causes a great deal of variance in the methods used for designing, manufacturing, and operating the research instruments.

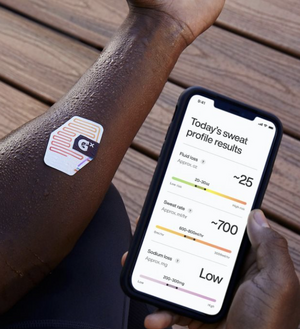

Optical sweat sensors typically work by allowing perspiration to enter certain channels and/or holes inside the microfluidic chip. Several reagents can be used to detect various components of perspiration. These holes are filled with reagents created to give a colorimetric response. Usually, a strong, vivid colorimetric response is produced when the component being tested is present in high concentration. Also, these optical sweat sensors may frequently be accurately scanned with a smartphone or can be lightly inspected by sight. This ease of use can be seen in Figure 4 displaying an optical sweat sensor and its phone app counterpart. The key advantages of optical sweat sensors are that they are often affordable, portable, and straightforward gadgets. The majority of optical sweat sensors, however, have the limitation of being unable to monitor changes in sweat composition over time. [10],[11]

Soft Sensors

Soft Sensors are currently being researched and developed due to the many advantages that come with flexibility of such a device.[12] These types of sensors can better fit to an object and detect more effectively even when stretched. Soft sensors have many biomedical applications which include health-monitoring, wearable devices, artificial skin, and intelligent robots. The human skin to sensor interface is improved with a flexible and stretchable device since the human body is constantly in movement and a better molding of a device to the body helps reduce sensing errors.

Liquid Metal Based Sensors

Liquid Metal Sensors are sensors that utilize liquid metal in their circuits. Typically liquid metal is used for properties such as flexibility, ability to be stretched, ease of application and various other magnetic, thermal, or electrochemical properties. Liquid-metal sensors have many unique properties that allow for the development of effective soft sensors. In comparison to rigid metals, liquid metals are deformable and fluidic. Some important properties of liquid metals include softness, high electrical conductivity, high thermal conductivity, and distinct interfacial chemistry.[13] Typical sensors use solid metal in their circuits and so have limited geometry as well as a static shape. Liquid metal sensors go a step beyond regular circuits as well as flexible ones in having conductive elements that are able to directly conform to the substrate and experience little to no strain (stretchable electronics). While liquid metal can be used in traditional sensors, appropriate utilization of the properties of liquid metals mentioned earlier can allow for some unique ways to sense various parameters, particularly in the biomedical field due to relative ease of conformation to curved surfaces.[12]

References

1. Radhakrishnan, S.; Mathew, M.; Sekhar Rout, C. Microfluidic Sensors Based on Two-Dimensional Materials for Chemical and Biological Assessments. Materials Advances 2022, 3 (4), 1874–1904. https://doi.org/10.1039/D1MA00929J.

2. Wu, J.; Gu, M. Microfluidic Sensing: State of the Art Fabrication and Detection Techniques. J Biomed Opt 2011, 16 (8), 080901. https://doi.org/10.1117/1.3607430.

3. Rossier, J.; Reymond, F.; Michel, P. Polymer Microfluidic Chips for Electrochemical and Biochemical Analyses. Electrophoresis 2002, 23, 858–867. https://doi.org/10.1002/1522-2683(200203)23:6<858::AID-ELPS858>3.0.CO;2-3.

4. Swensen, J. S.; Xiao, Y.; Ferguson, B. S.; Lubin, A. A.; Lai, R. Y.; Heeger, A. J.; Plaxco, K. W.; Soh, H. Tom. Continuous, Real-Time Monitoring of Cocaine in Undiluted Blood Serum via a Microfluidic, Electrochemical Aptamer-Based Sensor. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009, 131 (12), 4262–4266. https://doi.org/10.1021/ja806531z.

5. Pu, H.; Xiao, W.; Sun, D.-W. SERS-Microfluidic Systems: A Potential Platform for Rapid Analysis of Food Contaminants. Trends in Food Science & Technology 2017, 70, 114–126. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tifs.2017.10.001.

6. Pumera, M. Nanomaterials Meet Microfluidics. Chem. Commun. 2011, 47 (20), 5671–5680. https://doi.org/10.1039/C1CC11060H.

7. Stern, E.; Wagner, R.; Sigworth, F. J.; Breaker, R.; Fahmy, T. M.; Reed, M. A. Importance of the Debye Screening Length on Nanowire Field Effect Transistor Sensors. Nano Lett. 2007, 7 (11), 3405–3409. https://doi.org/10.1021/nl071792z.

8. Nguyen, H. H.; Lee, S. H.; Lee, U. J.; Fermin, C. D.; Kim, M. Immobilized Enzymes in Biosensor Applications. Materials 2019, 12 (1), 121. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma12010121.

9. Luka, G.; Ahmadi, A.; Najjaran, H.; Alocilja, E.; DeRosa, M.; Wolthers, K.; Malki, A.; Aziz, H.; Althani, A.; Hoorfar, M. Microfluidics Integrated Biosensors: A Leading Technology towards Lab-on-a-Chip and Sensing Applications. Sensors 2015, 15 (12), 30011–30031. https://doi.org/10.3390/s151229783.

10. Choi, J.; Bandodkar, A. J.; Reeder, J. T.; Ray, T. R.; Turnquist, A.; Kim, S. B.; Nyberg, N.; Hourlier-Fargette, A.; Model, J. B.; Aranyosi, A. J.; Xu, S.; Ghaffari, R.; Rogers, J. A. Soft, Skin-Integrated Multifunctional Microfluidic Systems for Accurate Colorimetric Analysis of Sweat Biomarkers and Temperature. ACS Sens. 2019, 4 (2), 379–388. https://doi.org/10.1021/acssensors.8b01218.

11. Nyein, H. Y. Y.; Bariya, M.; Kivimäki, L.; Uusitalo, S.; Liaw, T. S.; Jansson, E.; Ahn, C. H.; Hangasky, J. A.; Zhao, J.; Lin, Y.; Happonen, T.; Chao, M.; Liedert, C.; Zhao, Y.; Tai, L.-C.; Hiltunen, J.; Javey, A. Regional and Correlative Sweat Analysis Using High-Throughput Microfluidic Sensing Patches toward Decoding Sweat. Science Advances 2019, 5 (8), eaaw9906. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.aaw9906.

12. Ren, Y.; Sun, X.; Liu, J. Advances in Liquid Metal-Enabled Flexible and Wearable Sensors. Micromachines (Basel) 2020, 11 (2), 200. https://doi.org/10.3390/mi11020200.

13. Baharfar, M.; Kalantar-Zadeh, K. Emerging Role of Liquid Metals in Sensing. ACS Sens. 2022, 7 (2), 386–408. https://doi.org/10.1021/acssensors.1c02606.