User:Andy Maloney/Water isotope effects on kinesin and microtubules: Difference between revisions

Andy Maloney (talk | contribs) |

|||

| (19 intermediate revisions by 2 users not shown) | |||

| Line 7: | Line 7: | ||

* [[User_talk:Andy_Maloney|Click here to post general comments about the open dissertation]]. | * [[User_talk:Andy_Maloney|Click here to post general comments about the open dissertation]]. | ||

* [[User_talk:Andy_Maloney/Water_isotope_effects_on_kinesin_and_microtubules|Click here to post comments to this chapter's talk page]]. | * [[User_talk:Andy_Maloney/Water_isotope_effects_on_kinesin_and_microtubules|Click here to post comments to this chapter's talk page]]. | ||

A pdf version of the Introduction can be [http://www.openwetware.org/wiki/Image:AMDissertation_Chapter_4.pdf downloaded here]. This is the final snapshot of the dissertation that has been approved by my committee. This file will inevitably become out of sync with the wiki pages. | |||

A zip folder containing the LaTeX code can be down loaded [http://www.openwetware.org/images/9/95/Chapter_4_-_Water_istotopes.zip here]. | |||

<br style="clear:both;"/> | |||

==Acknowledgements== | |||

I would like to thank Dr. Haiqing Liu (while in the lab of [http://cint.lanl.gov/gabriel_montano.shtml Dr. Gabriel A. Montano]) for supplying kinesin to our lab. I would also like to thank [http://panda.unm.edu/pandaweb/people/person.phtml?personID=76 Dr. Susan Atlas] and the support from DTRA CB Basic Research Program under Grant No. HDTRA1-09-1-008 and the UNM IGERT on Integrating Nanotechnology with Cell Biology and Neuroscience NSF Grant DGE-0549500. Finally, I'd like to thank [http://www.biotec.tu-dresden.de/research/schaeffer/ Dr. Erik Schaeffer] for his discussions on temperature stabilization. | |||

<br style="clear:both;"/> | <br style="clear:both;"/> | ||

==Introduction== | ==Introduction== | ||

Water is a crucial component to biomolecular interactions that is often overlooked (Parsegian 1995). It can easily get through the lipid bilayer of cellular membranes. Cells are very densely packed and are regulated via protein generation and ion pumps so that they maintain a certain osmotic pressure. When cells are placed in a hypoosmotic environment, water will permeate the membrane such that the osmotic pressure inside the cell and outside it, balance. This can cause the cell to swell with water. The reverse case can occur as well when a cell is placed in a hyperosmotic environment. In this case, the water in the cell will leave | Water is a crucial component to biomolecular interactions that is often overlooked (Parsegian 1995). It can easily get through the lipid bilayer of cellular membranes. Cells are very densely packed and are regulated via protein generation and ion pumps so that they maintain a certain osmotic pressure. When cells are placed in a hypoosmotic environment, water will permeate the membrane such that the osmotic pressure inside the cell and outside it, balance. This can cause the cell to swell with water. The reverse case can occur as well when a cell is placed in a hyperosmotic environment. In this case, the water in the cell will leave in order to try and equilibriate the osmotic pressure differences. This causes the cell to shrink. | ||

Water is needed for peptide hydrolysis and ATP hydrolysis. Kinesin | Water is needed for peptide hydrolysis and ATP hydrolysis. Kinesin uses water to hydrolyze ATP so that it can take steps along microtubules. Water is crucial for life and is necessary for many chemical reactions in cells. Water hydrates all protein membranes and has been found to be present when EcoRI non specifically binds to DNA (Parsegian 1995). When EcoRI does bind to the DNA, those water molecules that were in between the DNA and enzyme are expelled into the bulk water so that EcoRI can bind to the DNA. In order for the kinesin motor domain to bind to the microtubule during a step, it is reasonable to suggest that if it is hydrated, those water molecules would have to move from the protein surface to become bulk water molecules. | ||

The work described in this chapter investigated if osmotic pressure changes can be observed using different isotopes of water while investigating the kinesin and microtubule system. | |||

<br style="clear:both;"/> | <br style="clear:both;"/> | ||

==Methods and materials== | ==Methods and materials== | ||

Most of this section is identical to previous chapters. I will only describe the differences done with this assay in this section while linking to the relevant components from other chapters below. | Most of this section is identical to previous chapters. I will only describe the differences done with this assay in this section while linking to the relevant components from other chapters below. | ||

* [http://www.openwetware.org/wiki/User:Andy_Maloney/Kinesin_%26_Microtubule_Page#Microscope_and_image_acquisition_software Microscope & Image acquisition software] | * [http://www.openwetware.org/wiki/User:Andy_Maloney/Kinesin_%26_Microtubule_Page#Microscope_and_image_acquisition_software Microscope & Image acquisition software] | ||

* [http://www.openwetware.org/wiki/User:Andy_Maloney/Surface_passivation_effects_on_kinesin_and_microtubules#Temperature_stabilization Temperature stabilization] | * [http://www.openwetware.org/wiki/User:Andy_Maloney/Surface_passivation_effects_on_kinesin_and_microtubules#Temperature_stabilization Temperature stabilization] | ||

* [http://www.openwetware.org/wiki/User:Andy_Maloney/Kinesin_%26_Microtubule_Page#The_PEM_buffer PEM buffer] | * [http://www.openwetware.org/wiki/User:Andy_Maloney/Kinesin_%26_Microtubule_Page#The_PEM_buffer PEM buffer] | ||

* [http://www.openwetware.org/wiki/User:Andy_Maloney/Kinesin_%26_Microtubule_Page#Antifade Antifade] & [http://www.openwetware.org/wiki/User:Andy_Maloney/Kinesin_%26_Microtubule_Page#PEM-Glu PEM-Glu] | * [http://www.openwetware.org/wiki/User:Andy_Maloney/Kinesin_%26_Microtubule_Page#Antifade Antifade] & [http://www.openwetware.org/wiki/User:Andy_Maloney/Kinesin_%26_Microtubule_Page#PEM-Glu PEM-Glu] | ||

* [http://www.openwetware.org/wiki/User:Andy_Maloney/Kinesin_%26_Microtubule_Page#Tubulin Tubulin] for [http://www.openwetware.org/wiki/User:Andy_Maloney/Kinesin_%26_Microtubule_Page#Microtubule_polymerization Microtubule polymerization] & [http://www.openwetware.org/wiki/User:Andy_Maloney/Kinesin_%26_Microtubule_Page#Taxol Taxol] for microtubule stabilization. | * [http://www.openwetware.org/wiki/User:Andy_Maloney/Kinesin_%26_Microtubule_Page#Tubulin Tubulin] for [http://www.openwetware.org/wiki/User:Andy_Maloney/Kinesin_%26_Microtubule_Page#Microtubule_polymerization Microtubule polymerization] & [http://www.openwetware.org/wiki/User:Andy_Maloney/Kinesin_%26_Microtubule_Page#Taxol Taxol] for microtubule stabilization. | ||

* [http://www.openwetware.org/wiki/User:Andy_Maloney/Kinesin_%26_Microtubule_Page#Kinesin Kinesin] & [http://www.openwetware.org/wiki/User:Andy_Maloney/Kinesin_%26_Microtubule_Page#PEM-A PEM-A] | * [http://www.openwetware.org/wiki/User:Andy_Maloney/Kinesin_%26_Microtubule_Page#Kinesin Kinesin] & [http://www.openwetware.org/wiki/User:Andy_Maloney/Kinesin_%26_Microtubule_Page#PEM-A PEM-A] | ||

* [http://www.openwetware.org/wiki/User:Andy_Maloney/Surface_passivation_effects_on_kinesin_and_microtubules#.CE.B1-PEM α-PEM]. | * [http://www.openwetware.org/wiki/User:Andy_Maloney/Surface_passivation_effects_on_kinesin_and_microtubules#.CE.B1-PEM α-PEM]. | ||

* Flow cells | * Flow cells | ||

* New PEM buffers using different isotopes of water. | * New PEM buffers using different isotopes of water. | ||

The differences for these experiments as compared to others I've done are subtle, however, they make a big difference to the assay. The measurable differences in how the assay responds to different environments is not too surprising considering how sensitive it is to ionic strength and pH (Bohm 2000b). | |||

The differences for these experiments as compared to others I've done are subtle, however, they make a big difference to the assay. The measurable differences in how the assay responds to different environments is not too surprising considering how sensitive it is to ionic strength and pH ( | |||

<br style="clear:both;"/> | <br style="clear:both;"/> | ||

===New flow cells=== | ===New flow cells=== | ||

The construction of the new flow cells was very similar to the old construction. The only difference was that I intended for the new flow cells to not be permanently sealed. This required finding a material that would | The construction of the new flow cells was very similar to the old construction. The only difference was that I intended for the new flow cells to not be permanently sealed. This required finding a material that would ''seal'' the flow cell in order to prevent evaporation and at the same time allow me to observe it on the microscope, remove it from the microscope, and flow in new material to be observed again. Surprisingly enough, plain old kitchen plastic wrap (cellophane) worked the best at this task. | ||

{| border="0" align="center" valign="bottom" cellpadding=10px | {| border="0" align="center" valign="bottom" cellpadding=10px | ||

|- | |- | ||

| Line 38: | Line 45: | ||

| align="left" | [[Image:AM SlideVertical.JPG|200px]] | | align="left" | [[Image:AM SlideVertical.JPG|200px]] | ||

|- | |- | ||

| align="left" valign="top" width="300" | '''Step 2:''' I added strips of permanent double stick tape ([http://www.scotchbrand.com/wps/portal/3M/en_US/ScotchBrand/Scotch/Products/ProductCatalog/?PC_7_RJH9U52300LM30I87QR3ES18H7_nid=B3KLCRZFWBgsTF1RRQ4PQRgl2FFHH0HTHSbl Scotch]) to the slide by using the two most center lines as a guide. This created a channel that is approximately 10 | | align="left" valign="top" width="300" | '''Step 2:''' I added strips of permanent double stick tape ([http://www.scotchbrand.com/wps/portal/3M/en_US/ScotchBrand/Scotch/Products/ProductCatalog/?PC_7_RJH9U52300LM30I87QR3ES18H7_nid=B3KLCRZFWBgsTF1RRQ4PQRgl2FFHH0HTHSbl Scotch]) to the slide by using the two most center lines as a guide. This created a channel that is approximately 10 μL in volume. The width of the two center lines was 5 mm. | ||

| align="left" | [[Image:AM SlideTape2.JPG|200px]] | | align="left" | [[Image:AM SlideTape2.JPG|200px]] | ||

|- | |- | ||

| Line 47: | Line 54: | ||

| align="left" | [[Image:AM CoverSlipAdhered.JPG|200px]] | | align="left" | [[Image:AM CoverSlipAdhered.JPG|200px]] | ||

|- | |- | ||

| align="left" valign="top" width="300" | '''Step 5:''' If the flow cell was not intended to be used as a resealable one, then it was finished | | align="left" valign="top" width="300" | '''Step 5:''' If the flow cell was not intended to be used as a resealable one, then it was finished Step 4. If it was intended to be used with the cellophane sealer, then I continued on with the following steps. Two very thin pieces of double stick tape were placed at the entrances of the flow cell. They have been colored red in the image to enhance contrast. These pieces of tape were essential for proper sealing with a piece of cellophane and helped prevent the objective oil from seeping into the flow cell. They can be made by holding two razor blades together and cutting a thin piece of tape. I had to ensure that the thin pieces of tape were as close as possible to the entrances of the flow cell since I observed excess evaporation occurred if they were not close. | ||

| align="left" | [[Image:AM TapeStrips.JPG|200px]] | | align="left" | [[Image:AM TapeStrips.JPG|200px]] | ||

|- | |- | ||

| Line 53: | Line 60: | ||

| align="left" | [[Image:AM Celophane.JPG|200px]] | | align="left" | [[Image:AM Celophane.JPG|200px]] | ||

|} | |} | ||

I should note that I also tried static cling vinyl and pallet wrap before settling on using cellophane. The static cling vinyl was not used because it was too thick and did not properly seal the flow cell. But, it did indicate to me that the static cling was what I wanted to use as the new sealer for the flow cells. This lead me to pallet wrap which was not used because it contains a small amount of glue and I did not want that glue seeping into my flow cells. Using it did show me that I needed a thinner material to | I should note that I also tried static cling vinyl and pallet wrap before settling on using cellophane. The static cling vinyl was not used because it was too thick and did not properly seal the flow cell. But, it did indicate to me that the static cling was what I wanted to use as the new sealer for the flow cells. This lead me to pallet wrap which was not used because it contains a small amount of glue and I did not want that glue seeping into my flow cells. Using it did show me that I needed a thinner material to ''seal'' the flow cell with and ultimately lead to the use of cellophane that can be purchased at a grocery store. | ||

There has been some debate about the use of nail polish as the sealant for flow cells due to the organic solvents that are in them. Using both the nail polish sealant method and this new cellophane seal method (which has no chemicals that could possibly leach into the flow cell) did not show a difference in the observed gliding motility speeds. I will discuss this in greater detail and show a figure below in the Results section. | There has been some debate about the use of nail polish as the sealant for flow cells due to the organic solvents that are in them. Using both the nail polish sealant method and this new cellophane seal method (which has no chemicals that could possibly leach into the flow cell) did not show a difference in the observed gliding motility speeds. I will discuss this in greater detail and show a figure below in the Results section. | ||

<br style="clear:both;"/> | <br style="clear:both;"/> | ||

===New solutions=== | ===New solutions=== | ||

Along with the 10x concentrated solution of PEM mixed in 18.2 MΩ-cm water, I prepared three other solutions containing two different isotopes of water, namely D<sub>2</sub>O and H<sub>2</sub><sup>18</sup>O and one sample with water that contained ≤ 1 ppm of D<sub>2</sub>O | Along with the 10x concentrated solution of PEM mixed in 18.2 MΩ-cm water, I prepared three other solutions containing two different isotopes of water, namely D<sub>2</sub>O and H<sub>2</sub><sup>18</sup>O, and one sample with water that deuterium depleted and contained ≤ 1 ppm of D<sub>2</sub>O. The reason for changing the water isotope was to try and measure speed differences dependent on the water isotope concentration in solution. The goal was to try and see if we could somehow relate the change in water isotopes to an increase in osmotic pressure of the system. I will discuss this more in the following sections however, the data is leading me to believe that I measured a viscosity change and not an osmotic pressure change. | ||

<br style="clear:both;"/> | <br style="clear:both;"/> | ||

====D<sub>2</sub>O overview==== | ====D<sub>2</sub>O overview==== | ||

D<sub>2</sub>O has some rather remarkable properties that are completely different than the properties of regular water. For instance, D<sub>2</sub>O | {| border="0" align="right" valign="bottom" cellpadding=10px | ||

|- | |||

| align="left" | [[Image:TobaccoSeeds.jpg|300px]] | |||

|- | |||

| align="left" valign="top" width="300" | '''Figure 1:''' Recreation of the work done by Lewis in the 1930s. The cuvette on the left has tobacco seeds that have been soaking in 100% D<sub>2</sub>O for 19 days and the one on the right has tobacco seeds that have been soaking in deionized water for 19 days. There is no apparent growth of the seeds in the left cuvette while there is definite growth in the seeds on the right. | |||

|} | |||

D<sub>2</sub>O has some rather remarkable properties that are completely different than the properties of regular water. For instance, D<sub>2</sub>O has the following properties (Hoefs 1987, Soper 2008, Katz 1957). | |||

* 20 - 25% more viscous than H<sub>2</sub>O. | |||

* 10% more dense than H<sub>2</sub>O. | |||

* Boils at 101.42°C. | |||

* Freezes at 3.81°C. | |||

* Intermolecular bond longer than H<sub>2</sub>O. | |||

* Number of bonds in D<sub>2</sub>O ≈ 3.76. | |||

* Number of bonds in H<sub>2</sub>O ≈ 3.62. | |||

* ≈ $1/gram at 99.9% purity. | |||

The density of D<sub>2</sub>O compared to the density of H<sub>2</sub>O is easily visualized by how frozen D<sub>2</sub>O will sink in a solution of H<sub>2</sub>O. D<sub>2</sub>O has also been shown to stabilize tubulin (Chakrabarti 1999, Das 2008) and is known to prevent microtubules from depolymerizing (Panda 2000). It is used in the thermal stabilization of vaccines (Sen 2009) and can even be used to make fruit flies more tolerant to heat (Pittendrigh 1974). Rhodamine has been shown to have better photostability in heavy hydrogen water as well (Sinha 2002). It is also known to prevent cellular growth without changing the permeability of cellular walls to water (Lucke 1935, Lewis 1933, Lewis 1934). Deuterium is such an odd isotopic species that there have even been studies showing that a lack of deuterium during growth causes stunting (Somlyai 1993). In order to investigate the effects of D<sub>2</sub>O on growth, I have started a side project that is attempting to recreate the seminal work done by Lewis (Lewis 1933, Lewis 1934). Preliminary data shows that growth is affected by D<sub>2</sub>O as can be seen in Figure 1. | |||

Some work has been done on investigating how molecular motors act in a solution of D<sub>2</sub>O (Chaen 2001). Chaen et al. also showed that when they reduced the amount of ATP in solution such that it became the rate limiting step, the speed at which actomyosin converted ATP was less than the speed in H<sub>2</sub>O. | |||

Some work has been done on investigating how molecular motors act in a solution of D<sub>2</sub>O (Chaen 2001). Chaen et | |||

<br style="clear:both;"/> | <br style="clear:both;"/> | ||

====H-PEM recipe==== | ====H-PEM recipe==== | ||

No studies have been made on how water isotopes affect kinesin and microtubules. To remedy this, I took data looking at the speed at which microtubules glide at in the presence of D<sub>2</sub>O. | No studies have been made on how water isotopes affect kinesin and microtubules. To remedy this, I took data looking at the speed at which microtubules glide at in the presence of D<sub>2</sub>O. I prepared a solution of PEM in D<sub>2</sub>O which I called H-PEM to indicate that it contained the heavy hydrogen isotope of water. H-PEM was made in a 10x concentrated solution and contained the following. | ||

* 800 mM of [http://www.sigmaaldrich.com/catalog/ProductDetail.do?lang=en&N4=80635|SIGMA&N5=SEARCH_CONCAT_PNO|BRAND_KEY&F=SPEC PIPES] (6.0474 g PIPES) | * 800 mM of [http://www.sigmaaldrich.com/catalog/ProductDetail.do?lang=en&N4=80635|SIGMA&N5=SEARCH_CONCAT_PNO|BRAND_KEY&F=SPEC PIPES] (6.0474 g PIPES) | ||

* 10 mM of [http://www.sigmaaldrich.com/catalog/ProductDetail.do?lang=en&N4=03778|FLUKA&N5=SEARCH_CONCAT_PNO|BRAND_KEY&F=SPEC EGTA] (.0951 g EGTA) | * 10 mM of [http://www.sigmaaldrich.com/catalog/ProductDetail.do?lang=en&N4=03778|FLUKA&N5=SEARCH_CONCAT_PNO|BRAND_KEY&F=SPEC EGTA] (.0951 g EGTA) | ||

| Line 76: | Line 96: | ||

* [http://www.sigmaaldrich.com/catalog/ProductDetail.do?lang=en&N4=151882|ALDRICH&N5=SEARCH_CONCAT_PNO|BRAND_KEY&F=SPEC D<sub>2</sub>O] | * [http://www.sigmaaldrich.com/catalog/ProductDetail.do?lang=en&N4=151882|ALDRICH&N5=SEARCH_CONCAT_PNO|BRAND_KEY&F=SPEC D<sub>2</sub>O] | ||

I used NaOH to pH the solution but, pH is a concentration measurement of hydrogen ions in solution and not deuterium ions. In order to measure the correct | I used NaOH to pH the solution but, pH is a concentration measurement of hydrogen ions in solution and not deuterium ions. In order to measure the correct ''pD'' of this solution using the pH meter, I had to add 0.41 to the measured value (Covington 1968). This meant that the solution of PEM in D<sub>2</sub>O was pH-ed to 7.30 using NaOH. H-PEM was passed through a 0.2 μm syringe filter, aliquoted, and then stored at 4°C in screw top vials. | ||

*[[User:Steven J. Koch|Steve Koch]] 00:14, 27 August 2011 (EDT): NOTE!!! I am thinking that this is a mistake and the buffer should have been made to 6.48 !!! See: http://friendfeed.com/anthonysalvagno/dbc577ae/preliminary-tobacco-seed-growth-results-those | |||

<br style="clear:both;"/> | <br style="clear:both;"/> | ||

====H<sub>2</sub><sup>18</sup>O overview==== | ====H<sub>2</sub><sup>18</sup>O overview==== | ||

Heavy oxygen water | Heavy oxygen water has the following properties (Hoefs 1987, Soper 2008, Kudish 1972). | ||

* 5% more viscous than H<sub>2</sub>O. | |||

* 11% more dense than H<sub>2</sub>O. | |||

* Boils at 100.14°C. | |||

* Freezes at 0.28°C. | |||

* $200/gram at 97% purity. | |||

There is not much in the literature about heavy oxygen water other than it is used extensively in labeling (Schwartz 2007, Dawis 1989). Its diffusion through regular H<sub>2</sub><sup>16</sup>O water has been measured as well (Easteal 1984). I believe that the lack of research using H<sub>2</sub><sup>18</sup>O is probably due to its high cost. A single gram of water with 97% atomic purity of <sup>18</sup>O costs $200. A gram with 99% atomic purity of <sup>18</sup>O costs nearly $1000 at the time of this writing. With this type of cost prohibitions, I had to change the way I prepared PEM in H<sub>2</sub><sup>18</sup>O. | |||

<br style="clear:both;"/> | <br style="clear:both;"/> | ||

====O-PEM recipe==== | ====O-PEM recipe==== | ||

| Line 92: | Line 119: | ||

<br style="clear:both;"/> | <br style="clear:both;"/> | ||

====D-PEM recipe==== | ====D-PEM recipe==== | ||

In order to maintain the absolute minimum amount of D<sub>2</sub>O in any solution, all solutions were remade with the deuterium depleted water. This meant remaking the following solutions in deuterium depleted water (D-H<sub>2</sub>O). | Our reasoning behind investigating this one data point was two fold. We wanted to see what would happen if there was an almost zero amount of D<sub>2</sub>O in solution and to use the deuterium depleted water for our tobacco seed experiment. In order to maintain the absolute minimum amount of D<sub>2</sub>O in any solution, all solutions were remade with the deuterium depleted water. This meant remaking the following solutions in deuterium depleted water (D-H<sub>2</sub>O). | ||

* 10x PEM in [http://www.sigmaaldrich.com/catalog/ProductDetail.do?lang=en&N4=195294|ALDRICH&N5=SEARCH_CONCAT_PNO|BRAND_KEY&F=SPEC D-H<sub>2</sub>O] (10x D-PEM) | * 10x PEM in [http://www.sigmaaldrich.com/catalog/ProductDetail.do?lang=en&N4=195294|ALDRICH&N5=SEARCH_CONCAT_PNO|BRAND_KEY&F=SPEC D-H<sub>2</sub>O] (10x D-PEM) --- This meant preparing a 1 M solution of [http://www.sigmaaldrich.com/catalog/ProductDetail.do?lang=en&N4=449172|ALDRICH&N5=SEARCH_CONCAT_PNO|BRAND_KEY&F=SPEC MgCl<sub>2</sub>] in D-H<sub>2</sub>O. | ||

* 1.0 mg/mL α-casein in D-PEM (α-DPEM) | * 1.0 mg/mL α-casein in D-PEM (α-DPEM) | ||

* 0.5 mg/mL α-casein in D-PEM (DPEM- | * 0.5 mg/mL α-casein in D-PEM (DPEM-) | ||

* 100 mM ATP in D-PEM (DPEM-A) | * 100 mM ATP in D-PEM (DPEM-A) | ||

* 2 M glucose in D-PEM (DPEM-Glu) | * 2 M glucose in D-PEM (DPEM-Glu) | ||

| Line 103: | Line 129: | ||

* 8 mg/mL catalase in D-PEM (DPEM-CAT) | * 8 mg/mL catalase in D-PEM (DPEM-CAT) | ||

* Antifade using DPEM-GOD and DPEM-CAT | * Antifade using DPEM-GOD and DPEM-CAT | ||

Preparation of these samples was conducted in the same manner outlined in [http://www.openwetware.org/wiki/User:Andy_Maloney/Kinesin_%26_Microtubule_Page Chapter 2]. The only differences with what was mentioned in [http://www.openwetware.org/wiki/User:Andy_Maloney/Kinesin_%26_Microtubule_Page Chapter 2] and this assay was that I had to mix up a 1 M solution of MgCl<sub>2</sub>. Adding MgCl<sub>2</sub> to water produces a highly exothermic reaction and much to my surprise, I found out how exothermic this reaction was. | |||

The only possible sources of D<sub>2</sub>O came from the kinesin, which the stock solution was not stored in deuterium depleted water, and/or from the microtubules since the tubulin was stored in [http://www.openwetware.org/wiki/User:Andy_Maloney/Kinesin_%26_Microtubule_Page#Tubulin_Suspension_Buffer_.28TSB.29_overview TSB] which did not use deuterium depleted water. | |||

<br style="clear:both;"/> | <br style="clear:both;"/> | ||

==Experiment and data analysis== | ==Experiment and data analysis== | ||

The experimental procedure and data analysis is nearly identical to the steps taken in [http://www.openwetware.org/wiki/User:Andy_Maloney/Surface_passivation_effects_on_kinesin_and_microtubules Chapter | The experimental procedure and data analysis of this experiment is nearly identical to the steps taken in [http://www.openwetware.org/wiki/User:Andy_Maloney/Surface_passivation_effects_on_kinesin_and_microtubules Chapter 3]. Below, I will outline the experimental procedure since it does differ from what was done there and is relevant to the discussion. However, I will only link to the data analysis section of [http://www.openwetware.org/wiki/User:Andy_Maloney/Surface_passivation_effects_on_kinesin_and_microtubules Chapter 3] below. | ||

<br style="clear:both;"/> | <br style="clear:both;"/> | ||

===Experiment=== | ===Experiment=== | ||

| Line 115: | Line 143: | ||

# Incubated the flow cell with 1.0 mg/mL alpha casein in PEM for 10 minutes. | # Incubated the flow cell with 1.0 mg/mL alpha casein in PEM for 10 minutes. | ||

# During the 10 minute incubation, [http://www.openwetware.org/wiki/User:Andy_Maloney/Kinesin_%26_Microtubule_Page#Kinesin kinesin] was diluted in 0.5 mg/mL [http://www.openwetware.org/wiki/User:Andy_Maloney/Surface_passivation_effects_on_kinesin_and_microtubules#.CE.B1-PEM α-casein] in PEM plus 1 mM ATP. The final concentration of kinesin used in these experiments was 27.5 μg/mL. | # During the 10 minute incubation, [http://www.openwetware.org/wiki/User:Andy_Maloney/Kinesin_%26_Microtubule_Page#Kinesin kinesin] was diluted in 0.5 mg/mL [http://www.openwetware.org/wiki/User:Andy_Maloney/Surface_passivation_effects_on_kinesin_and_microtubules#.CE.B1-PEM α-casein] in PEM plus 1 mM ATP. The final concentration of kinesin used in these experiments was 27.5 μg/mL. | ||

# After 10 minutes, kinesin was flowed into the flow cell by fluid exchange. The volume of the flow cell was approximately 10 μL. To ensure that all the fluid in the flow cell was exchanged | # After 10 minutes, kinesin was flowed into the flow cell by fluid exchange. The volume of the flow cell was approximately 10 μL. To ensure that all the fluid in the flow cell was exchanged, 20 μL of the kinesin mixture was flowed into the chamber. This was then allowed to sit for 5 minutes. | ||

# During the various incubation steps, a new motility solution was prepared for each assay. The motility assays consisted of: | # During the various incubation steps, a new motility solution was prepared for each assay. The motility assays consisted of: | ||

#* 1 μL of [http://www.openwetware.org/wiki/User:Andy_Maloney/Kinesin_%26_Microtubule_Page#PEM-A PEM-A]. | #* 1 μL of [http://www.openwetware.org/wiki/User:Andy_Maloney/Kinesin_%26_Microtubule_Page#PEM-A PEM-A]. | ||

| Line 121: | Line 149: | ||

#* 2.5 μL of [http://www.openwetware.org/wiki/User:Andy_Maloney/Kinesin_%26_Microtubule_Page#Antifade Antifade]. | #* 2.5 μL of [http://www.openwetware.org/wiki/User:Andy_Maloney/Kinesin_%26_Microtubule_Page#Antifade Antifade]. | ||

#* 0.1 μL of [http://www.openwetware.org/wiki/User:Andy_Maloney/Kinesin_%26_Microtubule_Page#Taxol Taxol]. | #* 0.1 μL of [http://www.openwetware.org/wiki/User:Andy_Maloney/Kinesin_%26_Microtubule_Page#Taxol Taxol]. | ||

#* Some percentage of either | #* Some percentage of either O-PEM or H-PEM. | ||

#* The necessary volume of [http://www.openwetware.org/wiki/User:Andy_Maloney/Kinesin_%26_Microtubule_Page#The_PEM_buffer PEM] required to make the motility solution a final volume of 100.1 μL. | #* The necessary volume of [http://www.openwetware.org/wiki/User:Andy_Maloney/Kinesin_%26_Microtubule_Page#The_PEM_buffer PEM] required to make the motility solution a final volume of 100.1 μL. | ||

#* 5 μL of [http://www.openwetware.org/wiki/User:Andy_Maloney/Kinesin_%26_Microtubule_Page#Microtubule_polymerization microtubules]. | #* 5 μL of [http://www.openwetware.org/wiki/User:Andy_Maloney/Kinesin_%26_Microtubule_Page#Microtubule_polymerization microtubules]. | ||

| Line 127: | Line 155: | ||

# The flow cell was either sealed with nail polish or cellophane dependent on which assay was to be performed. | # The flow cell was either sealed with nail polish or cellophane dependent on which assay was to be performed. | ||

After sealing the flow cell, the slide was immediately placed on the microscope for observation. For a detailed description of why I used these parameters, please see [http://www.openwetware.org/wiki/User:Andy_Maloney/Surface_passivation_effects_on_kinesin_and_microtubules Chapter | After sealing the flow cell, the slide was immediately placed on the microscope for observation. For a detailed description of why I used these parameters, please see [http://www.openwetware.org/wiki/User:Andy_Maloney/Surface_passivation_effects_on_kinesin_and_microtubules Chapter 3]. Briefly, the camera was set to take images as follows. | ||

* 600 total frames which was approximately 2 minutes total exposure. | * 600 total frames which was approximately 2 minutes total exposure for a single ROI. | ||

* EMCCD gain of 150. | * EMCCD gain of 150. | ||

* 100 ms single exposure. | * 100 ms single exposure. | ||

| Line 135: | Line 163: | ||

====D-PEM assay==== | ====D-PEM assay==== | ||

The same steps to produce the D-PEM assays were taken as was outlined above. I will list how the D-PEM assay was performed such that possible sources of D<sub>2</sub>O can be highlighted. | The same steps to produce the D-PEM assays were taken as was outlined above. I will list how the D-PEM assay was performed such that possible sources of D<sub>2</sub>O can be highlighted. | ||

# A flow cell was made and incubated with α-DPEM for 10 minutes. | # A flow cell was made and incubated with α-DPEM for 10 minutes. | ||

# During the casein incubation, a dilution of kinesin in DPEM-αA was made. I added 2 μL of the kinesin stock to the DPEM-αA solution. The final concentration of kinesin was again 27.5 μg/mL, however, this step gives a possible source of D<sub>2</sub>O. | # During the casein incubation, a dilution of kinesin in DPEM-αA was made. I added 2 μL of the kinesin stock to the DPEM-αA solution. The final concentration of kinesin was again 27.5 μg/mL, however, this step gives a possible source of D<sub>2</sub>O. | ||

| Line 146: | Line 175: | ||

#* 5 μL of polymerized microtubules that were fixed in a solution of 10 μM Taxol in D-PEM. | #* 5 μL of polymerized microtubules that were fixed in a solution of 10 μM Taxol in D-PEM. | ||

# After the 5 minute incubation, 20 μL of the motility solution was added to the flow cell. | # After the 5 minute incubation, 20 μL of the motility solution was added to the flow cell. | ||

# The flow cell was sealed and immediately observed on the microscope. | # The flow cell was sealed with nail polish and immediately observed on the microscope. | ||

The sources of D<sub>2</sub>O from this assay come from the kinesin and motility solution steps. Presumably, the fluid exchange from the kinesin to the motility solutions removes all the fluid from | |||

The sources of D<sub>2</sub>O from this assay come from the kinesin and motility solution steps. Presumably, the fluid exchange from the kinesin to the motility solutions removes all the fluid from the flow cell. If it does, then the only source of D<sub>2</sub>O in the assay would come from the TSB. The tubulin stored and polymerized in TSB is diluted by 200% when fixed with Taxol after polymerization. Those microtubules are again diluted into the motility solution by 95%. This leaves an approximate percentage of 0.5% of possible D<sub>2</sub>O contamination, or 0.04 mM of D<sub>2</sub>O in solution.The maximum possible contaminant concentration of D<sub>2</sub>O in this solution is 20% or 1.6 mM. | |||

<br style="clear:both;"/> | <br style="clear:both;"/> | ||

===Data analysis=== | ===Data analysis=== | ||

Please see [http://www.openwetware.org/wiki/User:Andy_Maloney/Surface_passivation_effects_on_kinesin_and_microtubules | Please see [http://www.openwetware.org/wiki/User:Andy_Maloney/Surface_passivation_effects_on_kinesin_and_microtubules Chapter 3]'s data analysis section for a detailed description of how the data was analyzed. | ||

<br style="clear:both;"/> | <br style="clear:both;"/> | ||

==Results and discussion== | ==Results and discussion== | ||

===Results=== | ===Results=== | ||

| Line 158: | Line 190: | ||

| align="left" | [[Image:AM D2O.jpg|300px]] | | align="left" | [[Image:AM D2O.jpg|300px]] | ||

|- | |- | ||

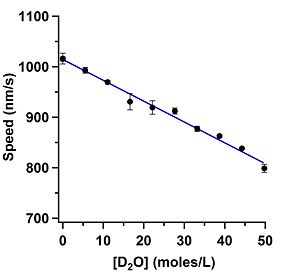

| align="left" valign="top" width="300" | '''Figure | | align="left" valign="top" width="300" | '''Figure 2:''' Graph showing the gliding speed dependence of microtubules when D<sub>2</sub>O was added to the motility solution. | ||

|- | |- | ||

| align="left" | [[Image:AM H218O.jpg|300px]] | | align="left" | [[Image:AM H218O.jpg|300px]] | ||

|- | |- | ||

| align="left" valign="top" width="300" | '''Figure | | align="left" valign="top" width="300" | '''Figure 3:''' Graph showing the gliding speed dependence of microtubules when H<sub>2</sub><sup>18</sup>O was added to the motility solution. | ||

|- | |- | ||

| align="left" | [[Image:AM ReflowCell.jpg|300px]] | | align="left" | [[Image:AM ReflowCell.jpg|300px]] | ||

|- | |- | ||

| align="left" valign="top" width="300" | '''Figure | | align="left" valign="top" width="300" | '''Figure 4:''' Graph showing the gliding speed dependence of microtubules using the resealable flow cell. Data was taken using 0% concentration of H-PEM then 90% concentration of H-PEM and back to a 0% concentration. | ||

|} | |} | ||

Each slide was observed for a total of 15 fields of view, or about 30 minutes for each slide. Assays were run at 10% increments of H-PEM added to the motility solution starting from 0% and ending with 90%. Each 10% increment was then run a total of 3 times. For each slide, only the last 10 fields of view were kept to compute an average speed value for that assay. The first 5 data points were removed due to the increase in temperature of the slide from room temperature (24°C) to the objective at 33.1°C | Each slide was observed for a total of 15 fields of view, or about 30 minutes for each slide. Assays were run at 10% increments of H-PEM added to the motility solution starting from 0% and ending with 90%. Each 10% increment was then run a total of 3 times. For each slide, only the last 10 fields of view were kept to compute an average speed value for that assay. The first 5 data points were removed due to the increase in temperature of the slide from room temperature (24°C) to the objective at 33.1°C. Averaging those 10 data points gave a single data point for the assay. Each assay was then run three separate times. This gave a total of 3 average velocity data points that were the accumulation of hundreds of tracked microtubules for a single assay. | ||

Each data point in Figure | Each data point in Figure 2 is the average of those 3 speed measurements and the error bars are the standard error of the mean (SEM). The concentration of D<sub>2</sub>O was calculated by first converting the percentage values of H-PEM used in the motility assay to concentration values in one mole of H<sub>2</sub>O. Next, the baseline amount of D<sub>2</sub>O in water was calculated to be 8 mM (Somlyai 1993). The 8 mM baseline was then added to the concentration of H-PEM used. | ||

The assay that used D-PEM as the buffer gave a speed value that was indistinguishable from the | The assay that used D-PEM as the buffer gave a speed value that was indistinguishable from the ''zero'' value that had 0% H-PEM as the solution, 1015 nm/s. This result was as expected noting how linear Figure 2 is. | ||

Exchanging the D<sub>2</sub>O for H<sub>2</sub><sup>18</sup>O in the motility solutions also showed a remarkably linear graph, Figure | Exchanging the D<sub>2</sub>O for H<sub>2</sub><sup>18</sup>O in the motility solutions also showed a remarkably linear graph, Figure 3. The concentration of H<sub>2</sub><sup>18</sup>O was calculated in a similar fashion as was the D<sub>2</sub>O concentration. | ||

Data taken with the resealable flow cells that used cellophane as the | Data taken with the resealable flow cells that used cellophane as the ''sealant'' is shown in Figure 4. The small grey markers are the speed measurements for the individual assays that were conducted. The blue lines are the average speed measurements determined from those assays using the same methodology described above. The first cluster of data are speed measurements using no H-PEM in solution. The second, is when the 0% H-PEM solution in the flow cell was exchanged with 90% H-PEM. The third cluster is when the 90% H-PEM was exchanged for 0% H-PEM. | ||

<br style="clear:both;"/> | <br style="clear:both;"/> | ||

===Discussion=== | ===Discussion=== | ||

The linearity of the assays run with D<sub>2</sub>O and H<sub>2</sub><sup>18</sup>O are quite remarkable. The decrease in speed for the D<sub>2</sub>O assay is about 21% and the decrease in the H<sub>2</sub><sup>18</sup> assay is about 5%. The viscosity of | The linearity of the assays run with D<sub>2</sub>O and H<sub>2</sub><sup>18</sup>O are quite remarkable. The decrease in speed for the D<sub>2</sub>O assay is about 21% and the decrease in the H<sub>2</sub><sup>18</sup>O assay is about 5%. The viscosity of D<sub>2</sub>O is about 20% greater than H<sub>2</sub>O while H<sub>2</sub><sup>18</sup>O is 5% greater than H<sub>2</sub>O. The speed differences measured would suggest (in light of the viscosity numbers) that we measured a viscous change in the solvent and not an osmotic pressure change. If viscosity is the cause of the decrease in speed, then these results are quite remarkable as they indicate that gliding motility speeds can measure small viscous changes in solutions. More investigation needs to be done in order to fully understand what is happening because the results may not be due to a viscous effect. | ||

Kotyk et al. (Kotyk 1990) showed that ATP activity was not affected by the addition of D<sub>2</sub>O using yeast as the test subject. Our data would suggest that ATP activity of kinesin is also not affected by the addition of D<sub>2</sub>O. If ATP activity was hindered by the addition of D<sub>2</sub>O then I would have expected to see slower speeds than what I measured using D<sub>2</sub>O. I did not make any measurements using less than the 1 mM ATP in the motility solutions so ATP hydrolysis was never the rate limiting step. | |||

The use of nail polish as the flow cell sealant has been debated in our lab before. We use it because it is convenient and it works well. I have seen and heard of others using hot wax as the sealant and or even using glycerol. The data where I used cellophane as the flow cell sealant, shown in Figure 4, show that using nail polish as the sealant is completely acceptable since the first cluster of data points gave speed measurements that were similar to those done with nail polish. | |||

Figure 4 also shows that speed measurements using 90% H-PEM do not damage the system. The speed difference between the two 0% H-PEM washings is odd, however, and can probably be explained by not removing all the D<sub>2</sub>O in the flow cell. I washed the flow cell with only 2 sample volumes and there may be a change in measured speeds if more sample volumes were used in the washing. | |||

<br style="clear:both;"/> | <br style="clear:both;"/> | ||

==Conclusion== | ==Conclusion== | ||

The goal of this experiment was to investigate the kinesin and microtubule system using different isotopes of water. Our initial thought was that by changing the water, we would change the osmotic pressure of the system. The data | The goal of this experiment was to investigate the kinesin and microtubule system using different isotopes of water. Our initial thought was that by changing the water, we would change the osmotic pressure of the system. The data show that by changing the isotope of water used in the motility assay caused the gliding speeds of microtubules to change in a manner that we have not been able to determine a suitable description for. | ||

I also noted that using nail polish as the sealant for flow cells does not change the speed at which microtubules glide at. Nor does using D<sub>2</sub>O damage the system. | |||

<br style="clear:both;"/> | <br style="clear:both;"/> | ||

==Future work== | ==Future work== | ||

In order to measure osmotic pressure changes I can use two different osmolytes in the gliding motility assay that have very different viscosities. For example, glucose has a high viscosity as compared to betaine. Betaine is an osmolyte that your cells use to change their osmotic pressures. In order for betaine to have the same viscosity as a solution of glucose, I would have to use a lot more betaine than glucose. The concentration difference of glucose and betaine in the gliding motility assay would | In order to measure osmotic pressure changes I can use two different osmolytes in the gliding motility assay that have very different viscosities. For example, glucose has a high viscosity as compared to betaine. Betaine is an osmolyte that your cells use to change their osmotic pressures. In order for betaine to have the same viscosity as a solution of glucose, I would have to use a lot more betaine than glucose. The concentration difference of glucose and betaine in the gliding motility assay would mean that the two solutions would have different osmotic pressures. It will be interesting to see if I can measure speed differences using two solutions with different osmolyte concentrations that have the same viscosity. | ||

Finally, in order to ascertain if the speed differences measured using the resealable flow cell after washing with H-PEM is due to D<sub>2</sub>O contamination, I could redo the experiment except with a lot more fluid exchange than just two sample volumes. | |||

<font size=3>[http://www.openwetware.org/wiki/User:Andy_Maloney#Dissertation '''Return to the table of contents.''']</font> | |||

<font size=3>[http://www.openwetware.org/wiki/User:Andy_Maloney/Open_Science '''Forward to Chapter 4.''']</font> | |||

<br style="clear:both;"/> | <br style="clear:both;"/> | ||

Revision as of 21:15, 26 August 2011

Purpose

This page describes the experiment where I investigated gliding speed variations of microtubules using different water isotopes.

This is the third chapter in my completely open notebook science dissertation. If you would like to post questions, comments, or concerns, please join the wiki and post comments to the talk page. If you do not want to join the wiki and would still like to comment, feel free to email me.

- Click here to join the wiki.

- Click here to email me.

- Click here to post general comments about the open dissertation.

- Click here to post comments to this chapter's talk page.

A pdf version of the Introduction can be downloaded here. This is the final snapshot of the dissertation that has been approved by my committee. This file will inevitably become out of sync with the wiki pages.

A zip folder containing the LaTeX code can be down loaded here.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Dr. Haiqing Liu (while in the lab of Dr. Gabriel A. Montano) for supplying kinesin to our lab. I would also like to thank Dr. Susan Atlas and the support from DTRA CB Basic Research Program under Grant No. HDTRA1-09-1-008 and the UNM IGERT on Integrating Nanotechnology with Cell Biology and Neuroscience NSF Grant DGE-0549500. Finally, I'd like to thank Dr. Erik Schaeffer for his discussions on temperature stabilization.

Introduction

Water is a crucial component to biomolecular interactions that is often overlooked (Parsegian 1995). It can easily get through the lipid bilayer of cellular membranes. Cells are very densely packed and are regulated via protein generation and ion pumps so that they maintain a certain osmotic pressure. When cells are placed in a hypoosmotic environment, water will permeate the membrane such that the osmotic pressure inside the cell and outside it, balance. This can cause the cell to swell with water. The reverse case can occur as well when a cell is placed in a hyperosmotic environment. In this case, the water in the cell will leave in order to try and equilibriate the osmotic pressure differences. This causes the cell to shrink.

Water is needed for peptide hydrolysis and ATP hydrolysis. Kinesin uses water to hydrolyze ATP so that it can take steps along microtubules. Water is crucial for life and is necessary for many chemical reactions in cells. Water hydrates all protein membranes and has been found to be present when EcoRI non specifically binds to DNA (Parsegian 1995). When EcoRI does bind to the DNA, those water molecules that were in between the DNA and enzyme are expelled into the bulk water so that EcoRI can bind to the DNA. In order for the kinesin motor domain to bind to the microtubule during a step, it is reasonable to suggest that if it is hydrated, those water molecules would have to move from the protein surface to become bulk water molecules.

The work described in this chapter investigated if osmotic pressure changes can be observed using different isotopes of water while investigating the kinesin and microtubule system.

Methods and materials

Most of this section is identical to previous chapters. I will only describe the differences done with this assay in this section while linking to the relevant components from other chapters below.

- Microscope & Image acquisition software

- Temperature stabilization

- PEM buffer

- Antifade & PEM-Glu

- Tubulin for Microtubule polymerization & Taxol for microtubule stabilization.

- Kinesin & PEM-A

- α-PEM.

- Flow cells

- New PEM buffers using different isotopes of water.

The differences for these experiments as compared to others I've done are subtle, however, they make a big difference to the assay. The measurable differences in how the assay responds to different environments is not too surprising considering how sensitive it is to ionic strength and pH (Bohm 2000b).

New flow cells

The construction of the new flow cells was very similar to the old construction. The only difference was that I intended for the new flow cells to not be permanently sealed. This required finding a material that would seal the flow cell in order to prevent evaporation and at the same time allow me to observe it on the microscope, remove it from the microscope, and flow in new material to be observed again. Surprisingly enough, plain old kitchen plastic wrap (cellophane) worked the best at this task.

| Step 1: I created a template for fast and reproducible flow cell creation. Using my template, I centered a slide (VWR 48300-025) in the vertical rectangle. |

|

| Step 2: I added strips of permanent double stick tape (Scotch) to the slide by using the two most center lines as a guide. This created a channel that is approximately 10 μL in volume. The width of the two center lines was 5 mm. |

|

| Step 3: I trimed the excess tape by using the outer lines of the center box as a guide. I did not trim the tape such that the only tape left on the slide was in the center box. I only trimed the tape that hung over the slide. It turns out that keeping this extra tape is useful when making resealable flow cells. After trimming the tape I placed a cover slip (VWR 48366-045) over the center box. The center box was used as a guide to ensure that the cover slip was centered on the slide. |

|

| Step 4: I ensured proper adhesion of the cover slip to the tape by pressing it to the slide. Proper adhesion was done when the light that is scattered from the slide + tape + slip combo differs from when the slip is merely placed on the tape. Compare the figure from step 3 to this step and notice the difference in how the light scatters from the center box. |

|

| Step 5: If the flow cell was not intended to be used as a resealable one, then it was finished Step 4. If it was intended to be used with the cellophane sealer, then I continued on with the following steps. Two very thin pieces of double stick tape were placed at the entrances of the flow cell. They have been colored red in the image to enhance contrast. These pieces of tape were essential for proper sealing with a piece of cellophane and helped prevent the objective oil from seeping into the flow cell. They can be made by holding two razor blades together and cutting a thin piece of tape. I had to ensure that the thin pieces of tape were as close as possible to the entrances of the flow cell since I observed excess evaporation occurred if they were not close. |

|

| Step 6: Small strips of cellophane (Glad Cling Wrap) were then placed over the flow cells and wrapped around the slide. |

|

I should note that I also tried static cling vinyl and pallet wrap before settling on using cellophane. The static cling vinyl was not used because it was too thick and did not properly seal the flow cell. But, it did indicate to me that the static cling was what I wanted to use as the new sealer for the flow cells. This lead me to pallet wrap which was not used because it contains a small amount of glue and I did not want that glue seeping into my flow cells. Using it did show me that I needed a thinner material to seal the flow cell with and ultimately lead to the use of cellophane that can be purchased at a grocery store.

There has been some debate about the use of nail polish as the sealant for flow cells due to the organic solvents that are in them. Using both the nail polish sealant method and this new cellophane seal method (which has no chemicals that could possibly leach into the flow cell) did not show a difference in the observed gliding motility speeds. I will discuss this in greater detail and show a figure below in the Results section.

New solutions

Along with the 10x concentrated solution of PEM mixed in 18.2 MΩ-cm water, I prepared three other solutions containing two different isotopes of water, namely D2O and H218O, and one sample with water that deuterium depleted and contained ≤ 1 ppm of D2O. The reason for changing the water isotope was to try and measure speed differences dependent on the water isotope concentration in solution. The goal was to try and see if we could somehow relate the change in water isotopes to an increase in osmotic pressure of the system. I will discuss this more in the following sections however, the data is leading me to believe that I measured a viscosity change and not an osmotic pressure change.

D2O overview

D2O has some rather remarkable properties that are completely different than the properties of regular water. For instance, D2O has the following properties (Hoefs 1987, Soper 2008, Katz 1957).

- 20 - 25% more viscous than H2O.

- 10% more dense than H2O.

- Boils at 101.42°C.

- Freezes at 3.81°C.

- Intermolecular bond longer than H2O.

- Number of bonds in D2O ≈ 3.76.

- Number of bonds in H2O ≈ 3.62.

- ≈ $1/gram at 99.9% purity.

The density of D2O compared to the density of H2O is easily visualized by how frozen D2O will sink in a solution of H2O. D2O has also been shown to stabilize tubulin (Chakrabarti 1999, Das 2008) and is known to prevent microtubules from depolymerizing (Panda 2000). It is used in the thermal stabilization of vaccines (Sen 2009) and can even be used to make fruit flies more tolerant to heat (Pittendrigh 1974). Rhodamine has been shown to have better photostability in heavy hydrogen water as well (Sinha 2002). It is also known to prevent cellular growth without changing the permeability of cellular walls to water (Lucke 1935, Lewis 1933, Lewis 1934). Deuterium is such an odd isotopic species that there have even been studies showing that a lack of deuterium during growth causes stunting (Somlyai 1993). In order to investigate the effects of D2O on growth, I have started a side project that is attempting to recreate the seminal work done by Lewis (Lewis 1933, Lewis 1934). Preliminary data shows that growth is affected by D2O as can be seen in Figure 1.

Some work has been done on investigating how molecular motors act in a solution of D2O (Chaen 2001). Chaen et al. also showed that when they reduced the amount of ATP in solution such that it became the rate limiting step, the speed at which actomyosin converted ATP was less than the speed in H2O.

H-PEM recipe

No studies have been made on how water isotopes affect kinesin and microtubules. To remedy this, I took data looking at the speed at which microtubules glide at in the presence of D2O. I prepared a solution of PEM in D2O which I called H-PEM to indicate that it contained the heavy hydrogen isotope of water. H-PEM was made in a 10x concentrated solution and contained the following.

- 800 mM of PIPES (6.0474 g PIPES)

- 10 mM of EGTA (.0951 g EGTA)

- 10 mM of MgCl2 (250 μL MgCl2)

- ≈ 1.25 M NaOH

- D2O

I used NaOH to pH the solution but, pH is a concentration measurement of hydrogen ions in solution and not deuterium ions. In order to measure the correct pD of this solution using the pH meter, I had to add 0.41 to the measured value (Covington 1968). This meant that the solution of PEM in D2O was pH-ed to 7.30 using NaOH. H-PEM was passed through a 0.2 μm syringe filter, aliquoted, and then stored at 4°C in screw top vials.

- Steve Koch 00:14, 27 August 2011 (EDT): NOTE!!! I am thinking that this is a mistake and the buffer should have been made to 6.48 !!! See: http://friendfeed.com/anthonysalvagno/dbc577ae/preliminary-tobacco-seed-growth-results-those

H218O overview

Heavy oxygen water has the following properties (Hoefs 1987, Soper 2008, Kudish 1972).

- 5% more viscous than H2O.

- 11% more dense than H2O.

- Boils at 100.14°C.

- Freezes at 0.28°C.

- $200/gram at 97% purity.

There is not much in the literature about heavy oxygen water other than it is used extensively in labeling (Schwartz 2007, Dawis 1989). Its diffusion through regular H216O water has been measured as well (Easteal 1984). I believe that the lack of research using H218O is probably due to its high cost. A single gram of water with 97% atomic purity of 18O costs $200. A gram with 99% atomic purity of 18O costs nearly $1000 at the time of this writing. With this type of cost prohibitions, I had to change the way I prepared PEM in H218O.

O-PEM recipe

To prepare the PEM solution using heavy oxygen water I actually diluted the 10x PEM into the H218O water. This allowed me to make a solution of PEM containing 90% H218O. To make this solution I did the following.

- 100 μL of 10x PEM

- 900 μL of H218O

I should note that the vial in which H218O comes in makes it extremely difficult to remove all the material. Because of this, I was only able on average to acquire 850 μL of H218O water from a single vial. Using the techniques outlined in the previous chapters, I was able to run 30 different assays using varying amounts of H218O water in the assay with only 2 stock vials of heavy oxygen water. This solution was not pH-ed and it was not filtered for fear of loosing too much material in the filter. It aliquoted it and stored it at 3°C.

D-PEM recipe

Our reasoning behind investigating this one data point was two fold. We wanted to see what would happen if there was an almost zero amount of D2O in solution and to use the deuterium depleted water for our tobacco seed experiment. In order to maintain the absolute minimum amount of D2O in any solution, all solutions were remade with the deuterium depleted water. This meant remaking the following solutions in deuterium depleted water (D-H2O).

- 10x PEM in D-H2O (10x D-PEM) --- This meant preparing a 1 M solution of MgCl2 in D-H2O.

- 1.0 mg/mL α-casein in D-PEM (α-DPEM)

- 0.5 mg/mL α-casein in D-PEM (DPEM-)

- 100 mM ATP in D-PEM (DPEM-A)

- 2 M glucose in D-PEM (DPEM-Glu)

- 1 mM ATP in DPEM-α (DPEM-αA)

- 20 mg/mL glucose oxidase in D-PEM (DPEM-GOD)

- 8 mg/mL catalase in D-PEM (DPEM-CAT)

- Antifade using DPEM-GOD and DPEM-CAT

Preparation of these samples was conducted in the same manner outlined in Chapter 2. The only differences with what was mentioned in Chapter 2 and this assay was that I had to mix up a 1 M solution of MgCl2. Adding MgCl2 to water produces a highly exothermic reaction and much to my surprise, I found out how exothermic this reaction was.

The only possible sources of D2O came from the kinesin, which the stock solution was not stored in deuterium depleted water, and/or from the microtubules since the tubulin was stored in TSB which did not use deuterium depleted water.

Experiment and data analysis

The experimental procedure and data analysis of this experiment is nearly identical to the steps taken in Chapter 3. Below, I will outline the experimental procedure since it does differ from what was done there and is relevant to the discussion. However, I will only link to the data analysis section of Chapter 3 below.

Experiment

Experimental flow cells for observation were prepared as follows.

- Prepared a flow cell. Either the type to be sealed with nail polish or the type to be sealed with cellophane.

- Incubated the flow cell with 1.0 mg/mL alpha casein in PEM for 10 minutes.

- During the 10 minute incubation, kinesin was diluted in 0.5 mg/mL α-casein in PEM plus 1 mM ATP. The final concentration of kinesin used in these experiments was 27.5 μg/mL.

- After 10 minutes, kinesin was flowed into the flow cell by fluid exchange. The volume of the flow cell was approximately 10 μL. To ensure that all the fluid in the flow cell was exchanged, 20 μL of the kinesin mixture was flowed into the chamber. This was then allowed to sit for 5 minutes.

- During the various incubation steps, a new motility solution was prepared for each assay. The motility assays consisted of:

- After the 5 minute incubation with kinesin, 20 μL of the motility solution was introduced to the flow cell by fluid exchange.

- The flow cell was either sealed with nail polish or cellophane dependent on which assay was to be performed.

After sealing the flow cell, the slide was immediately placed on the microscope for observation. For a detailed description of why I used these parameters, please see Chapter 3. Briefly, the camera was set to take images as follows.

- 600 total frames which was approximately 2 minutes total exposure for a single ROI.

- EMCCD gain of 150.

- 100 ms single exposure.

- Frames were taken at 5 frames/second.

D-PEM assay

The same steps to produce the D-PEM assays were taken as was outlined above. I will list how the D-PEM assay was performed such that possible sources of D2O can be highlighted.

- A flow cell was made and incubated with α-DPEM for 10 minutes.

- During the casein incubation, a dilution of kinesin in DPEM-αA was made. I added 2 μL of the kinesin stock to the DPEM-αA solution. The final concentration of kinesin was again 27.5 μg/mL, however, this step gives a possible source of D2O.

- After 10 minutes, 20 μL of DPEM-αA + kinesin was flown into the flow cell and allowed to incubate for 5 minutes.

- During the incubation periods, a new motility solution was prepared containing the following.

- 90.5 μL of D-PEM

- 1 μL of DPEM-A

- 1 μL of DPEM-Glu

- 2.5 μL of antifade made from the DPEM-GOD & DPEM-CAT stocks.

- 0.1 μL of Taxol

- 5 μL of polymerized microtubules that were fixed in a solution of 10 μM Taxol in D-PEM.

- After the 5 minute incubation, 20 μL of the motility solution was added to the flow cell.

- The flow cell was sealed with nail polish and immediately observed on the microscope.

The sources of D2O from this assay come from the kinesin and motility solution steps. Presumably, the fluid exchange from the kinesin to the motility solutions removes all the fluid from the flow cell. If it does, then the only source of D2O in the assay would come from the TSB. The tubulin stored and polymerized in TSB is diluted by 200% when fixed with Taxol after polymerization. Those microtubules are again diluted into the motility solution by 95%. This leaves an approximate percentage of 0.5% of possible D2O contamination, or 0.04 mM of D2O in solution.The maximum possible contaminant concentration of D2O in this solution is 20% or 1.6 mM.

Data analysis

Please see Chapter 3's data analysis section for a detailed description of how the data was analyzed.

Results and discussion

Results

Each slide was observed for a total of 15 fields of view, or about 30 minutes for each slide. Assays were run at 10% increments of H-PEM added to the motility solution starting from 0% and ending with 90%. Each 10% increment was then run a total of 3 times. For each slide, only the last 10 fields of view were kept to compute an average speed value for that assay. The first 5 data points were removed due to the increase in temperature of the slide from room temperature (24°C) to the objective at 33.1°C. Averaging those 10 data points gave a single data point for the assay. Each assay was then run three separate times. This gave a total of 3 average velocity data points that were the accumulation of hundreds of tracked microtubules for a single assay.

Each data point in Figure 2 is the average of those 3 speed measurements and the error bars are the standard error of the mean (SEM). The concentration of D2O was calculated by first converting the percentage values of H-PEM used in the motility assay to concentration values in one mole of H2O. Next, the baseline amount of D2O in water was calculated to be 8 mM (Somlyai 1993). The 8 mM baseline was then added to the concentration of H-PEM used.

The assay that used D-PEM as the buffer gave a speed value that was indistinguishable from the zero value that had 0% H-PEM as the solution, 1015 nm/s. This result was as expected noting how linear Figure 2 is.

Exchanging the D2O for H218O in the motility solutions also showed a remarkably linear graph, Figure 3. The concentration of H218O was calculated in a similar fashion as was the D2O concentration.

Data taken with the resealable flow cells that used cellophane as the sealant is shown in Figure 4. The small grey markers are the speed measurements for the individual assays that were conducted. The blue lines are the average speed measurements determined from those assays using the same methodology described above. The first cluster of data are speed measurements using no H-PEM in solution. The second, is when the 0% H-PEM solution in the flow cell was exchanged with 90% H-PEM. The third cluster is when the 90% H-PEM was exchanged for 0% H-PEM.

Discussion

The linearity of the assays run with D2O and H218O are quite remarkable. The decrease in speed for the D2O assay is about 21% and the decrease in the H218O assay is about 5%. The viscosity of D2O is about 20% greater than H2O while H218O is 5% greater than H2O. The speed differences measured would suggest (in light of the viscosity numbers) that we measured a viscous change in the solvent and not an osmotic pressure change. If viscosity is the cause of the decrease in speed, then these results are quite remarkable as they indicate that gliding motility speeds can measure small viscous changes in solutions. More investigation needs to be done in order to fully understand what is happening because the results may not be due to a viscous effect.

Kotyk et al. (Kotyk 1990) showed that ATP activity was not affected by the addition of D2O using yeast as the test subject. Our data would suggest that ATP activity of kinesin is also not affected by the addition of D2O. If ATP activity was hindered by the addition of D2O then I would have expected to see slower speeds than what I measured using D2O. I did not make any measurements using less than the 1 mM ATP in the motility solutions so ATP hydrolysis was never the rate limiting step.

The use of nail polish as the flow cell sealant has been debated in our lab before. We use it because it is convenient and it works well. I have seen and heard of others using hot wax as the sealant and or even using glycerol. The data where I used cellophane as the flow cell sealant, shown in Figure 4, show that using nail polish as the sealant is completely acceptable since the first cluster of data points gave speed measurements that were similar to those done with nail polish.

Figure 4 also shows that speed measurements using 90% H-PEM do not damage the system. The speed difference between the two 0% H-PEM washings is odd, however, and can probably be explained by not removing all the D2O in the flow cell. I washed the flow cell with only 2 sample volumes and there may be a change in measured speeds if more sample volumes were used in the washing.

Conclusion

The goal of this experiment was to investigate the kinesin and microtubule system using different isotopes of water. Our initial thought was that by changing the water, we would change the osmotic pressure of the system. The data show that by changing the isotope of water used in the motility assay caused the gliding speeds of microtubules to change in a manner that we have not been able to determine a suitable description for.

I also noted that using nail polish as the sealant for flow cells does not change the speed at which microtubules glide at. Nor does using D2O damage the system.

Future work

In order to measure osmotic pressure changes I can use two different osmolytes in the gliding motility assay that have very different viscosities. For example, glucose has a high viscosity as compared to betaine. Betaine is an osmolyte that your cells use to change their osmotic pressures. In order for betaine to have the same viscosity as a solution of glucose, I would have to use a lot more betaine than glucose. The concentration difference of glucose and betaine in the gliding motility assay would mean that the two solutions would have different osmotic pressures. It will be interesting to see if I can measure speed differences using two solutions with different osmolyte concentrations that have the same viscosity.

Finally, in order to ascertain if the speed differences measured using the resealable flow cell after washing with H-PEM is due to D2O contamination, I could redo the experiment except with a lot more fluid exchange than just two sample volumes.

Return to the table of contents.

References

- Böhm, KJ, Stracke, R, & Unger, E (2000). Speeding up kinesin-driven microtubule gliding in vitro by variation of cofactor composition and physicochemical parameters. Cell biology international, 24(6), 335-41. doi: 10.1006/cbir.1999.0515.

- Chaen, S., Yamamoto, N., Shirakawa, I., & Sugi, H. (2001). Effect of deuterium oxide on actomyosin motility in vitro. Biochimica et biophysica acta, 1506(3), 218-23.

- Chakrabarti, G., Kim, S., Gupta, M. L., Barton, J. S., & Himes, R. H. (1999). Stabilization of tubulin by deuterium oxide. Biochemistry, 38(10), 3067-72. doi: 10.1021/bi982461r.

- Covington, A. K., Paabo, M., Robinson, R. A., & Bates, R. G. (1968). Use of the glass electrode in deuterium oxide and the relation between the standardized pD (paD) scale and the operational pH in heavy water. Analytical Chemistry, 40(4), 700-706. doi: 10.1021/ac60260a013.

- Das, A., Sinha, S., Acharya, B. R., Paul, P., Bhattacharyya, B., & Chakrabarti, G. (2008). Deuterium oxide stabilizes conformation of tubulin: a biophysical and biochemical study. BMB reports, 41(1), 62-7.

- Dawis, S. M., Walseth, T. F., Deeg, M. a, Heyman, R. a, Graeff, R. M., & Goldberg, N. D. (1989). Adenosine triphosphate utilization rates and metabolic pool sizes in intact cells measured by transfer of 18O from water. Biophysical journal, 55(1), 79-99. Elsevier. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(89)82782-1.

- Easteal, A. J., Edge, a V. J., & Woolf, L. a. (1984). Isotope effects in water. Tracer diffusion coefficients for water(oxygen-18) (H218O) in ordinary water. The Journal of Physical Chemistry, 88(24), 6060-6063. doi: 10.1021/j150668a065.

- Lewis, G. N. (1933). The biochemistry of water containing hydrogen isotope. Journal of the American Chemical Society, 55(8), 3503–3504. American Chemical Society. doi: 10.1021/ja01335a509.

- Katz, J. J., Crespi, H. L., Hasterlik, R. J., Thompson, J. F., & Finkel, A. J. (1957). Some observations on biological effects of deuterium, with special reference to effects on neoplastic processes. Journal of the National Cancer Institute, 18(5), 641-59.

- Kotyk, A., Dvoráková, M., & Koryta, J. (1990). Deuterons cannot replace protons in active transport processes in yeast. FEBS letters, 264(2), 203-5.

- Kudish, A. I., & Wolf, D. (1972). Physical Properties of Heavy-oxygen Water: Absolute Viscosity of H218O between 15 and 35°C. Journal of the Chemical Society, Faraday Transactions 1: Physical Chemistry in Condensed Phases, 68, 2041-2046.

- Lewis, G. N. (1934). The Biology of Heavy Water. Science (New York, N.Y.), 79(2042), 151-153. doi: 10.1126/science.79.2042.151.

- Lucké, B., & Harvey, E. N. (1935). The permeability of living cells to heavy water (deuterium oxide). Journal of Cellular and Comparative Physiology, 5(4), 473-482. doi: 10.1002/jcp.1030050407.

- Ozeki, T, Verma, V, Uppalapati, M, Suzuki, Y, Nakamura, M, Catchmark, JM, et al. (2009). Surface-bound casein modulates the adsorption and activity of kinesin on SiO2 surfaces. Biophysical journal, 96(8), 3305-18. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2008.12.3960.

- Panda, D., Chakrabarti, G., Hudson, J., Pigg, K., Miller, H. P., Wilson, L., et al. (2000). Suppression of microtubule dynamic instability and treadmilling by deuterium oxide. Biochemistry, 39(17), 5075-81.

- Parsegian, V. A., Rand, R. P., & Rau, D. C. (1995). [Parsegian, V. A., Rand, R. P., & Rau, D. C. (1995). Macromolecules and water: probing with osmotic stress. Methods in enzymology, 259. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8538466. Macromolecules and water: probing with osmotic stress]. Methods in enzymology, 259.

- Pittendrigh, C. S., & Cosbey, E. S. (1974). On the very rapid enhancement by D2O of the temperature-tolerance of adult Drosophila. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 71(2), 540-3.

- Sen, A., Balamurugan, V., Rajak, K. K., Chakravarti, S., Bhanuprakash, V., & Singh, R. K. (2009). Role of heavy water in biological sciences with an emphasis on thermostabilization of vaccines. Expert review of vaccines, 8(11), 1587-602. doi: 10.1586/erv.09.105.

- Sinha, S., Ray, a K., Kundu, S., Sasikumar, S., & Dasgupta, K. (2002). Heavy-water-based solutions of rhodamine dyes: photophysical properties and laser operation. Applied Physics B: Lasers and Optics, 75(1), 85-90. doi: 10.1007/s00340-002-0932-6.

- Somlyai, G., Jancsó, G., Jákli, G., Vass, K., Barna, B., Lakics, V., et al. (1993). Naturally occurring deuterium is essential for the normal growth rate of cells. FEBS letters, 317(1-2), 1-4.

- Schwartz, E. (2007). [http://aem.asm.org/cgi/content/short/73/8/2541 Characterization of growing microorganisms in soil by stable isotope probing with H218O. Applied and environmental microbiology, 73(8), 2541-6. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02021-06.