User:Victor Tapia: Difference between revisions

Victor Tapia (talk | contribs) |

Victor Tapia (talk | contribs) |

||

| (42 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 2: | Line 2: | ||

[[Image:Tapia_bewerbung.jpg|200px|right]] | [[Image:Tapia_bewerbung.jpg|200px|right]] | ||

<div style="padding: 10px; color: #000; background-color: #CEF2E0; width: 500px"> | <div style="padding: 10px; color: #000; background-color: #CEF2E0; width: 500px"> | ||

<br> | |||

Dr. rer. medic. <br> | |||

Víctor E . Tapia Mancilla <br> | Víctor E . Tapia Mancilla <br> | ||

Email: ve.tapia.m@gmail.com<br> | Email: ve.tapia.m@gmail.com <br> | ||

<br> | <br> | ||

Inst. f. Med. Immunol., <br> | |||

Charité - Universitätsmedizin Berlin, CCM <br> | |||

Hessische Str. 3-4, D-10115 Berlin <br> | |||

<br><br> | +49-30-450 524285 <br><br> | ||

Former institutions:<br> | Former institutions:<br> | ||

{{hide|<br> | {{hide|<br> | ||

| Line 23: | Line 25: | ||

Fax: +49-30-450 524962<br> | Fax: +49-30-450 524962<br> | ||

E-mail: rve@charite.de | E-mail: rve@charite.de | ||

<br><br>- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - <br><br> | <br><br>- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - <br><br> | ||

<br> | <br> | ||

| Line 39: | Line 40: | ||

Systems Immunology<br> | Systems Immunology<br> | ||

Michal Or-Guil<br> | Michal Or-Guil<br> | ||

<br><br>- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - <br><br> | |||

}} | }} | ||

Social networks<br> | |||

<br> | {{hide|<br> | ||

<br> | |||

<html> | <html> | ||

<a href="http://www.mendeley.com/profiles/ve-tapia"><img border="0" src="http://www.mendeley.com/embed/icon/2/red/small" alt="Bibliography manager"/></a> | <a href="http://www.mendeley.com/profiles/ve-tapia"><img border="0" src="http://www.mendeley.com/embed/icon/2/red/small" alt="Bibliography manager"/></a> | ||

</html><br> | </html><br> | ||

[http://victortapia.brandyourself.com jet another profile]<br> | [http://victortapia.brandyourself.com jet another profile]<br> | ||

[http://de.linkedin.com/pub/victor-tapia/29/285/a43 jet another other profile] | [http://de.linkedin.com/pub/victor-tapia/29/285/a43 jet another other profile]<br> | ||

[https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Victor_Tapia3]<br> | |||

<br>- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - <br><br> | |||

}} | |||

last actualization: 01.07.2014 | |||

</div> | |||

==Research interests== | |||

<!-- Feel free to add brief descriptions to your research interests as well --> | |||

[[Image:specprof.png|400px|right]] | |||

<div style="padding: 10px; color: #000; background-color: #CEF2E0; width: 500px"> | |||

1 | Specificity Profiles | |||

<br> | |||

A basic strategy to estimate the specificity of the protein recognition events | |||

involved in cellular signaling consists in defining an in vitro context of an | |||

extensive number of probes to define the specificity of protein recognition as | |||

a profile of biochemical binding potential (inherent specificity) and | |||

validating selected potential inter-actors via pull-down and co-localization | |||

experiments (effective specificity)[1,2]. | |||

<br> | |||

The modular analysis of specificity, i.e. focusing on interactions mediated by | |||

modules of protein structure[3,4], has been essential to our lab, allowing us | |||

to investigate the individual problems of several independent projects. The | |||

key point of this approach is the possibility to derive basic rules of peptide | |||

motif (PM) recognition in form of regular expressions characteristic for each | |||

peptide recognition module (PRM) family, with which matches in sequence | |||

databases can be searched. | |||

<br> | |||

In such cases we have strived a comprehensive[5,6], when not proteomic[7,8], | |||

profile of PMs recognized by individual or an homology family of PRMs. A | |||

specificity profile is firstly generated by establishing a collection of | |||

peptide probes, which represent matches of the regular expressions | |||

characteristic for a PRM family in a sequenced genome (Fig. 1, steps 1 and 2). | |||

High-throughput screening methods with a fluorescence scanner or a | |||

charge-coupled device camera can be applied to determine the capturing | |||

potential of each peptide probe for one or more analytes in a biological sample | |||

(Fig. 1, step 3). In this fashion, samples can be prepared with different | |||

PRMs and each sample can be profiled in terms of recognition specificity using | |||

an equal collection of probes[7,9]. Miniaturization of the assay platform or | |||

device, as with peptide micro-arrays, even allows simultaneous multiplex | |||

assays[10,11]. | |||

</div><br> | |||

[[Image:Pqbp1 arch.png|400px|right]] | |||

<div style="padding: 10px; color: #000; background-color: #CEF2E0; width: 500px"> | |||

2 | Modular Protein Recognition | |||

<br> | |||

Beyond learning specific aspects of protein function through gene ontology | |||

enrichment analysis[12,13], specificity profiles may also be applied to explore | |||

sets of elementary rules that are used to generate short linear motifs and the | |||

globular fold patterns of non-catalytic protein domains we have been calling | |||

PMs and PRMs, respectively. Understanding such rules governing protein | |||

recognition enables the prediction of ligands of particular biotechnological | |||

interest[14–16] and develop ways to exclusively modulate particular cellular | |||

pathologies[17–21]. | |||

<br> | |||

Most general lessons from work carried out to this date give the impression | |||

that founding paradigms of cellular signaling are abandoned. The observation | |||

that recognition events are of promiscuous nature has displaced the original | |||

notions of pathways built by highly specific binding between interacting | |||

partners[22]. | |||

<br> | |||

Indeed, each protein recognition domain exists in the cell simultaneously with | |||

a battery of similar domains and a large repertoire of promiscuous short linear | |||

motifs. Moreover, the binding affinity of native interactions are mostly weak | |||

at middle micro-molar range and can not be easily distinguished from competing | |||

interactions excluded from the network supporting a particular cellular | |||

response[2]. | |||

</div><br> | </div><br> | ||

[[Image:Rnp2-ctd-toolkit.png|400px|right]] | |||

<div style="padding: 10px; color: #000; background-color: #CEF2E0; width: 500px"> | |||

3 | Nature's Toolkit for Bioengineering | |||

<br> | |||

As a consequence cellular systems follow different strategies to regulate | |||

enzyme activity and evoke mutually exclusive cellular responses to different | |||

stimuli: (a) dynamic assembly of multi-protein complexes; (b) sub-cellular | |||

localization; and (c) temporal control. The modularity of protein structure is | |||

a well appreciated toolkit for biological engineers to address this matter in | |||

the context of synthetic biology or drug targeting[23–29]. | |||

<br> | |||

As example one may consider modular allosteric regulation of the RNA pol II via | |||

its C-terminal domain (RPII-CTD) at the downstream end of signal transduction | |||

(Fig. 2). RPII-CTD is an unstructured tail fragment that is | |||

post-transitionally modified by dedicated kinases[30,31]. These modifications | |||

are differentially recognized by a repertoire of PRMs across different homology | |||

families to regulate the activity of the multi-protein complex[32]. | |||

<br> | <br> | ||

Thus this systems provides a natural kit for bioengineers to design artificial | |||

combinations enzymatic modules with other modules for cellular localization and | |||

temporal control. Given knowledge of the recognition rules, these designed | |||

chimera can be combined to rewire the transcribing activity of RNA pol II[33]. | |||

The rules of binding recognition which need to be learned in order to account | |||

for effective specificity and mutually exclusive cellular responses go beyond | |||

visual strategies to describe the structure of compact recursive structural | |||

modules in proteins. They may more closely resemble rules for syntax, grammar, | |||

and semantics of human language[34–37]. | |||

</div><br> | |||

< | |||

<div style="padding: 10px; color: #000; background-color: #CEF2E0; width: 500px"> | <div style="padding: 10px; color: #000; background-color: #CEF2E0; width: 500px"> | ||

References | |||

<br> | |||

[1] J. E. Ladbury, S. Arold, Chem. Biol. 2000, 7, R3–R8.<br> | |||

[2] B. J. Mayer, J. Cell Sci. 2001, 114, 1253–1263.<br> | |||

[3] J. Janin, C. Chothia, in (Ed.: B.-M. in Enzymology), Academic Press, | |||

1985, pp. 420–430.<br> | |||

[4] J. Jin, X. Xie, C. Chen, J. G. Park, C. Stark, D. A. James, M. | |||

Olhovsky, R. Linding, Y. Mao, T. Pawson, Sci. Signal. 2009, 2, ra76–ra76.<br> | |||

[5] R. Tonikian, X. Xin, C. P. Toret, D. Gfeller, C. Landgraf, S. Panni, S. | |||

Paoluzi, L. Castagnoli, B. Currell, S. Seshagiri, et al., PLoS Biol. 2009, 7, | |||

e1000218.<br> | |||

[6] L. Vouilleme, P. R. Cushing, R. Volkmer, D. R. Madden, P. Boisguerin, | |||

Angew. Chem. Int. Ed Engl. 2010, 49, 9912–9916.<br> | |||

[7] V. E. Tapia, E. Nicolaescu, C. B. McDonald, V. Musi, T. Oka, Y. | |||

Inayoshi, A. C. Satteson, V. Mazack, J. Humbert, C. J. Gaffney, et al., J. | |||

Biol. Chem. 2010, 285, 19391–19401.<br> | |||

[8] A. Ulbricht, F. J. Eppler, V. E. Tapia, P. F. M. van der Ven, N. Hampe, | |||

N. Hersch, P. Vakeel, D. Stadel, A. Haas, P. Saftig, et al., Curr. Biol. CB | |||

2013, 23, 430–435.<br> | |||

[9] E. Verschueren, M. Spiess, A. Gkourtsa, T. Avula, C. Landgraf, V. T. | |||

Mancilla, A. Huber, R. Volkmer, B. Winsor, L. Serrano, et al., PLoS ONE 2015, | |||

10, e0129229.<br> | |||

[10] R. P. Ekins, Clin. Chem. 1998, 44, 2015–2030. | |||

[11] U. Reimer, U. Reineke, J. Schneider-Mergener, Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. | |||

2002, 13, 315–320.<br> | |||

[12] N. H. Shah, T. Cole, M. A. Musen, PLoS Comput. Biol. 2012, 8, DOI | |||

10.1371/journal.pcbi.1002827.<br> | |||

[13] M. Lavallée-Adam, N. Rauniyar, D. B. McClatchy, J. R. Yates, J. | |||

Proteome Res. 2014, 13, 5496–5509.<br> | |||

[14] J. Teyra, S. S. Sidhu, P. M. Kim, FEBS Lett. 2012, 586, 2631–2637.<br> | |||

[15] J. Reimand, S. Hui, S. Jain, B. Law, G. D. Bader, FEBS Lett. 2012, 586, | |||

2751–2763.<br> | |||

[16] E. Verschueren, P. Vanhee, F. Rousseau, J. Schymkowitz, L. Serrano, | |||

Structure 2013, 21, 789–797.<br> | |||

[17] N. A. Sallee, G. M. Rivera, J. E. Dueber, D. Vasilescu, R. D. Mullins, | |||

B. J. Mayer, W. A. Lim, Nature 2008, 454, 1005–1008.<br> | |||

[18] J. E. Dueber, B. J. Yeh, R. P. Bhattacharyya, W. A. Lim, Curr. Opin. | |||

Struct. Biol. 2004, 14, 690–699.<br> | |||

[19] L. E. M. Marengere, Z. Songyang, G. D. Gish, M. D. Schaller, J. T. | |||

Parsons, M. J. Stern, L. C. Cantley, T. Pawson, Nature 1994, 369, 502–505.<br> | |||

[20] P. L. Howard, M. C. Chia, S. Del Rizzo, F.-F. Liu, T. Pawson, Proc. | |||

Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2003, 100, 11267–11272.<br> | |||

[21] C. J. Bashor, A. A. Horwitz, S. G. Peisajovich, W. A. Lim, Annu. Rev. | |||

Biophys. 2010, 39, 515–537.<br> | |||

[22] B. J. Mayer, M. L. Blinov, L. M. Loew, J. Biol. 2009, 8, 81.<br> | |||

[23] R. P. Alexander, P. M. Kim, T. Emonet, M. B. Gerstein, Sci Signal 2009, | |||

2, pe44–pe44.<br> | |||

[24] A. Levskaya, O. D. Weiner, W. A. Lim, C. A. Voigt, Nature 2009, 461, | |||

997–1001.<br> | |||

[25] J. D. Scott, T. Pawson, Science 2009, 326, 1220–1224.<br> | |||

[26] R. Grünberg, L. Serrano, Nucleic Acids Res. 2010, 38, 2663–2675.<br> | |||

[27] D. Gfeller, F. Butty, M. Wierzbicka, E. Verschueren, P. Vanhee, H. | |||

Huang, A. Ernst, N. Dar, I. Stagljar, L. Serrano, et al., Mol. Syst. Biol. | |||

2011, 7, 484.<br> | |||

[28] R. Opitz, M. Müller, C. Reuter, M. Barone, A. Soicke, Y. Roske, K. | |||

Piotukh, P. Huy, M. Beerbaum, B. Wiesner, et al., Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. | |||

A. 2015, 112, 5011–5016.<br> | |||

[29] C. Corbi-Verge, P. M. Kim, Cell Commun. Signal. 2016, 14, 8.<br> | |||

[30] D. P. Morris, H. P. Phatnani, A. L. Greenleaf, J. Biol. Chem. 1999, | |||

274, 31583–31587.<br> | |||

[31] Y. Hirose, J. L. Manley, Genes Dev. 2000, 14, 1415–1429.<br> | |||

[32] B. T. Seet, I. Dikic, M.-M. Zhou, T. Pawson, Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. | |||

2006, 7, 473–483.<br> | |||

[33] B. Bartkowiak, C. Yan, A. L. Greenleaf, Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2015, | |||

1849, 1179–1187.<br> | |||

[34] J. S. Richardson, Nature 1977, 268, 495–500.<br> | |||

[35] D. B. Searls, Nature 2002, 420, 211–217.<br> | |||

[36] M. Gimona, Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2006, 7, 68–73.<br> | |||

[37] A. Scaiewicz, M. Levitt, Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 2015, 35, 50–56.<br> | |||

</div><br> | |||

==Message in a Bottle== | |||

[[Image:Hitchhicking-on-rnap2.png|400px|right]] | |||

<div style="padding: 10px; color: #000; background-color: #CEF2E0; width: 500px"> | |||

===ON TAPIA ET AL. 2010=== | |||

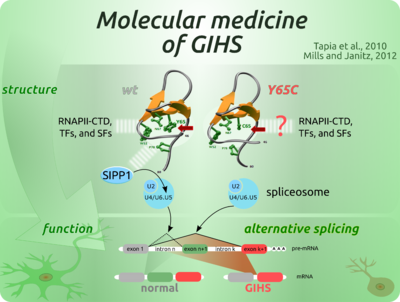

On a collaborative project concerning the role of PQBP1 in X-linked intellectual disability (X-LID), the inherent specificity of the wild-type and the Y65C-mutant PQBP1 WW were directly compared (Tapia et al., 2010). The collection of probes used to profile the linear motif recognition specificity contained a core repertoire of PPXY motifs and an additional tailor-made collection of non-PPXY potential ligands based on the literature. An independent comparison of the specificity of both WW versions was also carried out. Therein, the repertoire of probes represented a complete and redundant permutation of poS postitions in a sequence consensus of the CTD repeats in the human RNAPII (YS2PTS5PS-YS2PTS5PS). | |||

<br><br> | |||

Earlier reported interactions with phosphorylated CTD from RNAPII (Okazawa et al., 2002) and with SIPP1, a splicing factor interacting with Ser/Thr phosphatase-1 (PP1) protein (Llorian et al., 2005), were confirmed. Moreover, a comparison of wt and Y65C-mutant PQBP1 WW specificity profiles shows that the mutation, known to be associated with GIHS (Lubs et al., 2006), compromises the recognition of SIPP1. This effect was accordingly observed in cell extracts from HEK98 and lymphoblasts isolated from a GIHS patient (Figure 5A and B). Biophysical analysis of the mutation effect additionally showed a compromised thermal stability of the WW structure and reduced binding to SIPP1. | |||

<br><br> | |||

The consequences of the compromised PQBP1/SIPP1 complex was a significant reduction of pre-mRNA splicing, as shown in lymphoblasts derived from a GIHS patient. The decreased splicing efficiency was similar to that seen after small interfering RNA-mediated knockdown of PQBP1, indicating that PQBP1-Y65C is inactive in intact cells (Figure 5C-G). | |||

Moreover, Tapia et al. (2010) shows that the known WW-mediation of binding to RNAPII (Okazawa et al., 2002) depends on hyperphosphorylation of RNAPII's CTD. In the cell this is done by the pTEFb kinase complex, which thus imprints a post-translational marker for elongating RNAPII, known to recruit splicing factors (Batsché et al., 2006; Phatnani and Greenleaf, 2006). The orchestrating role of RNAPII in the cross-talk between transcription and splicing is well described (Bird et al., 2004; David and Manley, 2011; Neugebauer, 2002). | |||

<br><br> | |||

These findings provide additional empirical support for a role of PQBP1 in pre-mRNA splicing. Alternative splicing is particularly important in the brain, and a switch in alternative splicing patterns of primary transcripts encoding neuron-specific proteins is known to accompany neuronal differentiation (Fairbrother and Lipscombe, 2008; Lipscombe et al., 2013). Changes in alternative splice choices could, therefore, represent an important factor in the etiology of GIHS. More details in the involvement of PQBP1 and alternative splicing in neurodegeneration could be achieved upon identification of primary transcripts targeted by PQBP1-assisted alternative splicing (Wang et al., 2013). | |||

<br><br> | |||

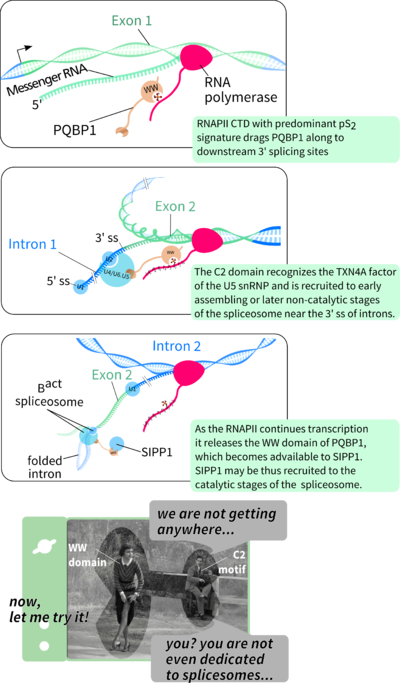

The diverse lesions in PQBP1 may lead to similar intelectual and morphological symptomes. Besides the Y65C point-mutation, all other X-LID associated PQBP1 mutation produce truncated proteins, which lack a C-terminal intrinsically unstructured domain known to bind the spliceosome assembling factor U5-15kDa. Such facts suggest that the WW domain of PQBP1 is sufficient to cause X-LID but not exclusively necessary as causative agent. It is posible that PQBP1 is firstly recruited by elongating RNAPII, then co-localizes to the assembling spliceosome through its C-terminal domain and, driven either by affinity or effective specificity, dynamic WW-mediated recognition may switch to SIPP1 binding to help activate the catalytic steps of pre-mRNA splicing. Alternatively, the role of RNAPII recognition may be secondary to the recognition of SIPP1, which has been shown to be shuttled to the nucleous independently from its own predicted nuclear localization signals, most possibly by PQBP1 (Llorian et al., 2005). Thus, under this model, PQBP1 functions as a scaffold between spliceosome assembly (C-terminal domain-mediated) and catalytic activity (WW-domain mediated). | |||

<br><br> | |||

This idea is apparently in paradox with the fact, that studies of PQBP1 involvement in intellectual disabilities using animal models show that Mus musculus and Drosophila melanogaster with knocked-down PQBP1 may be rescued from developing symptoms analogous to X-LID syndromes by applying HDAC inhibiting drugs (Ito et al., 2009; Tamura et al., 2010). Recent hypotheses of a cross-talk between chromatin remodelling and alternative splicing (Allemand et al., 2008) may shed some light on these findings. In the later citation, the authors are “tempted to speculate that the splicing machinery relies on chromatin regulators which are able to read the ‘histone code’ to locate and access pre-mRNAs awaiting splicing”. If they are given truth, the apparent paradox would turn to a further evidence. | |||

<br><br> | |||

Less conflictive are reports of PQBP1 transcription regulating activity through recognition of poly-Q expanded tracts in the transcription factors Brn-2 (Waragai et al., 1999) and ataxin-1 (Okazawa et al., 2002; Okuda et al., 2003). Indeed, SFs and TFs show common elements in their interaction networks and are oft erroneously categorized (Brès et al., 2005; Expert-Bezançon et al., 2002; Hastings et al., 2007). Poly-Q expanded ataxin-1 was shown to increases the affinity of the PQBP1-WW for the phosphorylated and active form of the RNAPII-CTD, leading to its dephosphorylation (Okazawa et al., 2002). Desphosphorylation on S2 and diffident reappearance of S5 phosphorylation on the CTD of eleongating RNAPII is known to slow down elongation rates and favor the recognition of weaker consensus sequences for splicing factor (de la Mata et al., 2003). Such situation favors the usage of alternative splicing patterns and the outcome of splicing variated gene products. | |||

<br><br> | <br><br> | ||

Thus, the empirical support for the involvement of PQBP1 in X-LID via alternative RNA splicing is found to fit and complement diverse empirical findings and theoretical postulates independently reported by different research laboratories. | |||

<br><br> | <br><br> | ||

Please take a look at the image to the right and set your mind for speculation. The image was produced in Inkscape using one of the wonderful SVG templates from Wikipedia User 'Kelvinsong'. | |||

</div><br> | |||

==Education== | ==Education== | ||

| Line 136: | Line 309: | ||

</div><br> | </div><br> | ||

==Useful links== | ==Useful links== | ||

| Line 180: | Line 320: | ||

*[http://meta.wikimedia.org/wiki/Help:Special_page wiki editing] | *[http://meta.wikimedia.org/wiki/Help:Special_page wiki editing] | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

Revision as of 03:45, 5 April 2016

Contact Information

Dr. rer. medic.

Víctor E . Tapia Mancilla

Email: ve.tapia.m@gmail.com

Inst. f. Med. Immunol.,

Charité - Universitätsmedizin Berlin, CCM

Hessische Str. 3-4, D-10115 Berlin

+49-30-450 524285

Former institutions:

Charité - Universitätsmedizin Berlin

Institut für medizinische Immunologie

AG Molekulare Bibliotheken

Dr. Rudolf Volkmer

Hessische Str. 3-4, 10115 Berlin

Tel.: +49-30-450 524267

oder +49-30-450 524317

Fax: +49-30-450 524962

E-mail: rve@charite.de

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

UMR7156 CNRS-Université de Strasbourg

Equipe Cytosquelette d'actine et Trafic intracellulaire

Département de Biologie moléculaire et cellulaire

Barbara Winsor, PhD

(† 29.09.2011)

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

Humboldt Universität, Berlin

Institute for Theoretical Biology

Systems Immunology

Michal Or-Guil

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

Social networks

<html>

<a href="http://www.mendeley.com/profiles/ve-tapia"><img border="0" src="http://www.mendeley.com/embed/icon/2/red/small" alt="Bibliography manager"/></a>

</html>

jet another profile

jet another other profile

[1]

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

last actualization: 01.07.2014

Research interests

1 | Specificity Profiles

A basic strategy to estimate the specificity of the protein recognition events

involved in cellular signaling consists in defining an in vitro context of an

extensive number of probes to define the specificity of protein recognition as

a profile of biochemical binding potential (inherent specificity) and

validating selected potential inter-actors via pull-down and co-localization

experiments (effective specificity)[1,2].

The modular analysis of specificity, i.e. focusing on interactions mediated by

modules of protein structure[3,4], has been essential to our lab, allowing us

to investigate the individual problems of several independent projects. The

key point of this approach is the possibility to derive basic rules of peptide

motif (PM) recognition in form of regular expressions characteristic for each

peptide recognition module (PRM) family, with which matches in sequence

databases can be searched.

In such cases we have strived a comprehensive[5,6], when not proteomic[7,8],

profile of PMs recognized by individual or an homology family of PRMs. A

specificity profile is firstly generated by establishing a collection of

peptide probes, which represent matches of the regular expressions

characteristic for a PRM family in a sequenced genome (Fig. 1, steps 1 and 2).

High-throughput screening methods with a fluorescence scanner or a

charge-coupled device camera can be applied to determine the capturing

potential of each peptide probe for one or more analytes in a biological sample

(Fig. 1, step 3). In this fashion, samples can be prepared with different

PRMs and each sample can be profiled in terms of recognition specificity using

an equal collection of probes[7,9]. Miniaturization of the assay platform or

device, as with peptide micro-arrays, even allows simultaneous multiplex

assays[10,11].

2 | Modular Protein Recognition

Beyond learning specific aspects of protein function through gene ontology

enrichment analysis[12,13], specificity profiles may also be applied to explore

sets of elementary rules that are used to generate short linear motifs and the

globular fold patterns of non-catalytic protein domains we have been calling

PMs and PRMs, respectively. Understanding such rules governing protein

recognition enables the prediction of ligands of particular biotechnological

interest[14–16] and develop ways to exclusively modulate particular cellular

pathologies[17–21].

Most general lessons from work carried out to this date give the impression

that founding paradigms of cellular signaling are abandoned. The observation

that recognition events are of promiscuous nature has displaced the original

notions of pathways built by highly specific binding between interacting

partners[22].

Indeed, each protein recognition domain exists in the cell simultaneously with

a battery of similar domains and a large repertoire of promiscuous short linear

motifs. Moreover, the binding affinity of native interactions are mostly weak

at middle micro-molar range and can not be easily distinguished from competing

interactions excluded from the network supporting a particular cellular

response[2].

3 | Nature's Toolkit for Bioengineering

As a consequence cellular systems follow different strategies to regulate

enzyme activity and evoke mutually exclusive cellular responses to different

stimuli: (a) dynamic assembly of multi-protein complexes; (b) sub-cellular

localization; and (c) temporal control. The modularity of protein structure is

a well appreciated toolkit for biological engineers to address this matter in

the context of synthetic biology or drug targeting[23–29].

As example one may consider modular allosteric regulation of the RNA pol II via

its C-terminal domain (RPII-CTD) at the downstream end of signal transduction

(Fig. 2). RPII-CTD is an unstructured tail fragment that is

post-transitionally modified by dedicated kinases[30,31]. These modifications

are differentially recognized by a repertoire of PRMs across different homology

families to regulate the activity of the multi-protein complex[32].

Thus this systems provides a natural kit for bioengineers to design artificial

combinations enzymatic modules with other modules for cellular localization and

temporal control. Given knowledge of the recognition rules, these designed

chimera can be combined to rewire the transcribing activity of RNA pol II[33].

The rules of binding recognition which need to be learned in order to account

for effective specificity and mutually exclusive cellular responses go beyond

visual strategies to describe the structure of compact recursive structural

modules in proteins. They may more closely resemble rules for syntax, grammar,

and semantics of human language[34–37].

References

[1] J. E. Ladbury, S. Arold, Chem. Biol. 2000, 7, R3–R8.

[2] B. J. Mayer, J. Cell Sci. 2001, 114, 1253–1263.

[3] J. Janin, C. Chothia, in (Ed.: B.-M. in Enzymology), Academic Press,

1985, pp. 420–430.

[4] J. Jin, X. Xie, C. Chen, J. G. Park, C. Stark, D. A. James, M.

Olhovsky, R. Linding, Y. Mao, T. Pawson, Sci. Signal. 2009, 2, ra76–ra76.

[5] R. Tonikian, X. Xin, C. P. Toret, D. Gfeller, C. Landgraf, S. Panni, S.

Paoluzi, L. Castagnoli, B. Currell, S. Seshagiri, et al., PLoS Biol. 2009, 7,

e1000218.

[6] L. Vouilleme, P. R. Cushing, R. Volkmer, D. R. Madden, P. Boisguerin,

Angew. Chem. Int. Ed Engl. 2010, 49, 9912–9916.

[7] V. E. Tapia, E. Nicolaescu, C. B. McDonald, V. Musi, T. Oka, Y.

Inayoshi, A. C. Satteson, V. Mazack, J. Humbert, C. J. Gaffney, et al., J.

Biol. Chem. 2010, 285, 19391–19401.

[8] A. Ulbricht, F. J. Eppler, V. E. Tapia, P. F. M. van der Ven, N. Hampe,

N. Hersch, P. Vakeel, D. Stadel, A. Haas, P. Saftig, et al., Curr. Biol. CB

2013, 23, 430–435.

[9] E. Verschueren, M. Spiess, A. Gkourtsa, T. Avula, C. Landgraf, V. T.

Mancilla, A. Huber, R. Volkmer, B. Winsor, L. Serrano, et al., PLoS ONE 2015,

10, e0129229.

[10] R. P. Ekins, Clin. Chem. 1998, 44, 2015–2030.

[11] U. Reimer, U. Reineke, J. Schneider-Mergener, Curr. Opin. Biotechnol.

2002, 13, 315–320.

[12] N. H. Shah, T. Cole, M. A. Musen, PLoS Comput. Biol. 2012, 8, DOI

10.1371/journal.pcbi.1002827.

[13] M. Lavallée-Adam, N. Rauniyar, D. B. McClatchy, J. R. Yates, J.

Proteome Res. 2014, 13, 5496–5509.

[14] J. Teyra, S. S. Sidhu, P. M. Kim, FEBS Lett. 2012, 586, 2631–2637.

[15] J. Reimand, S. Hui, S. Jain, B. Law, G. D. Bader, FEBS Lett. 2012, 586,

2751–2763.

[16] E. Verschueren, P. Vanhee, F. Rousseau, J. Schymkowitz, L. Serrano,

Structure 2013, 21, 789–797.

[17] N. A. Sallee, G. M. Rivera, J. E. Dueber, D. Vasilescu, R. D. Mullins,

B. J. Mayer, W. A. Lim, Nature 2008, 454, 1005–1008.

[18] J. E. Dueber, B. J. Yeh, R. P. Bhattacharyya, W. A. Lim, Curr. Opin.

Struct. Biol. 2004, 14, 690–699.

[19] L. E. M. Marengere, Z. Songyang, G. D. Gish, M. D. Schaller, J. T.

Parsons, M. J. Stern, L. C. Cantley, T. Pawson, Nature 1994, 369, 502–505.

[20] P. L. Howard, M. C. Chia, S. Del Rizzo, F.-F. Liu, T. Pawson, Proc.

Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2003, 100, 11267–11272.

[21] C. J. Bashor, A. A. Horwitz, S. G. Peisajovich, W. A. Lim, Annu. Rev.

Biophys. 2010, 39, 515–537.

[22] B. J. Mayer, M. L. Blinov, L. M. Loew, J. Biol. 2009, 8, 81.

[23] R. P. Alexander, P. M. Kim, T. Emonet, M. B. Gerstein, Sci Signal 2009,

2, pe44–pe44.

[24] A. Levskaya, O. D. Weiner, W. A. Lim, C. A. Voigt, Nature 2009, 461,

997–1001.

[25] J. D. Scott, T. Pawson, Science 2009, 326, 1220–1224.

[26] R. Grünberg, L. Serrano, Nucleic Acids Res. 2010, 38, 2663–2675.

[27] D. Gfeller, F. Butty, M. Wierzbicka, E. Verschueren, P. Vanhee, H.

Huang, A. Ernst, N. Dar, I. Stagljar, L. Serrano, et al., Mol. Syst. Biol.

2011, 7, 484.

[28] R. Opitz, M. Müller, C. Reuter, M. Barone, A. Soicke, Y. Roske, K.

Piotukh, P. Huy, M. Beerbaum, B. Wiesner, et al., Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S.

A. 2015, 112, 5011–5016.

[29] C. Corbi-Verge, P. M. Kim, Cell Commun. Signal. 2016, 14, 8.

[30] D. P. Morris, H. P. Phatnani, A. L. Greenleaf, J. Biol. Chem. 1999,

274, 31583–31587.

[31] Y. Hirose, J. L. Manley, Genes Dev. 2000, 14, 1415–1429.

[32] B. T. Seet, I. Dikic, M.-M. Zhou, T. Pawson, Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol.

2006, 7, 473–483.

[33] B. Bartkowiak, C. Yan, A. L. Greenleaf, Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2015,

1849, 1179–1187.

[34] J. S. Richardson, Nature 1977, 268, 495–500.

[35] D. B. Searls, Nature 2002, 420, 211–217.

[36] M. Gimona, Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2006, 7, 68–73.

[37] A. Scaiewicz, M. Levitt, Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 2015, 35, 50–56.

Message in a Bottle

ON TAPIA ET AL. 2010

On a collaborative project concerning the role of PQBP1 in X-linked intellectual disability (X-LID), the inherent specificity of the wild-type and the Y65C-mutant PQBP1 WW were directly compared (Tapia et al., 2010). The collection of probes used to profile the linear motif recognition specificity contained a core repertoire of PPXY motifs and an additional tailor-made collection of non-PPXY potential ligands based on the literature. An independent comparison of the specificity of both WW versions was also carried out. Therein, the repertoire of probes represented a complete and redundant permutation of poS postitions in a sequence consensus of the CTD repeats in the human RNAPII (YS2PTS5PS-YS2PTS5PS).

Earlier reported interactions with phosphorylated CTD from RNAPII (Okazawa et al., 2002) and with SIPP1, a splicing factor interacting with Ser/Thr phosphatase-1 (PP1) protein (Llorian et al., 2005), were confirmed. Moreover, a comparison of wt and Y65C-mutant PQBP1 WW specificity profiles shows that the mutation, known to be associated with GIHS (Lubs et al., 2006), compromises the recognition of SIPP1. This effect was accordingly observed in cell extracts from HEK98 and lymphoblasts isolated from a GIHS patient (Figure 5A and B). Biophysical analysis of the mutation effect additionally showed a compromised thermal stability of the WW structure and reduced binding to SIPP1.

The consequences of the compromised PQBP1/SIPP1 complex was a significant reduction of pre-mRNA splicing, as shown in lymphoblasts derived from a GIHS patient. The decreased splicing efficiency was similar to that seen after small interfering RNA-mediated knockdown of PQBP1, indicating that PQBP1-Y65C is inactive in intact cells (Figure 5C-G).

Moreover, Tapia et al. (2010) shows that the known WW-mediation of binding to RNAPII (Okazawa et al., 2002) depends on hyperphosphorylation of RNAPII's CTD. In the cell this is done by the pTEFb kinase complex, which thus imprints a post-translational marker for elongating RNAPII, known to recruit splicing factors (Batsché et al., 2006; Phatnani and Greenleaf, 2006). The orchestrating role of RNAPII in the cross-talk between transcription and splicing is well described (Bird et al., 2004; David and Manley, 2011; Neugebauer, 2002).

These findings provide additional empirical support for a role of PQBP1 in pre-mRNA splicing. Alternative splicing is particularly important in the brain, and a switch in alternative splicing patterns of primary transcripts encoding neuron-specific proteins is known to accompany neuronal differentiation (Fairbrother and Lipscombe, 2008; Lipscombe et al., 2013). Changes in alternative splice choices could, therefore, represent an important factor in the etiology of GIHS. More details in the involvement of PQBP1 and alternative splicing in neurodegeneration could be achieved upon identification of primary transcripts targeted by PQBP1-assisted alternative splicing (Wang et al., 2013).

The diverse lesions in PQBP1 may lead to similar intelectual and morphological symptomes. Besides the Y65C point-mutation, all other X-LID associated PQBP1 mutation produce truncated proteins, which lack a C-terminal intrinsically unstructured domain known to bind the spliceosome assembling factor U5-15kDa. Such facts suggest that the WW domain of PQBP1 is sufficient to cause X-LID but not exclusively necessary as causative agent. It is posible that PQBP1 is firstly recruited by elongating RNAPII, then co-localizes to the assembling spliceosome through its C-terminal domain and, driven either by affinity or effective specificity, dynamic WW-mediated recognition may switch to SIPP1 binding to help activate the catalytic steps of pre-mRNA splicing. Alternatively, the role of RNAPII recognition may be secondary to the recognition of SIPP1, which has been shown to be shuttled to the nucleous independently from its own predicted nuclear localization signals, most possibly by PQBP1 (Llorian et al., 2005). Thus, under this model, PQBP1 functions as a scaffold between spliceosome assembly (C-terminal domain-mediated) and catalytic activity (WW-domain mediated).

This idea is apparently in paradox with the fact, that studies of PQBP1 involvement in intellectual disabilities using animal models show that Mus musculus and Drosophila melanogaster with knocked-down PQBP1 may be rescued from developing symptoms analogous to X-LID syndromes by applying HDAC inhibiting drugs (Ito et al., 2009; Tamura et al., 2010). Recent hypotheses of a cross-talk between chromatin remodelling and alternative splicing (Allemand et al., 2008) may shed some light on these findings. In the later citation, the authors are “tempted to speculate that the splicing machinery relies on chromatin regulators which are able to read the ‘histone code’ to locate and access pre-mRNAs awaiting splicing”. If they are given truth, the apparent paradox would turn to a further evidence.

Less conflictive are reports of PQBP1 transcription regulating activity through recognition of poly-Q expanded tracts in the transcription factors Brn-2 (Waragai et al., 1999) and ataxin-1 (Okazawa et al., 2002; Okuda et al., 2003). Indeed, SFs and TFs show common elements in their interaction networks and are oft erroneously categorized (Brès et al., 2005; Expert-Bezançon et al., 2002; Hastings et al., 2007). Poly-Q expanded ataxin-1 was shown to increases the affinity of the PQBP1-WW for the phosphorylated and active form of the RNAPII-CTD, leading to its dephosphorylation (Okazawa et al., 2002). Desphosphorylation on S2 and diffident reappearance of S5 phosphorylation on the CTD of eleongating RNAPII is known to slow down elongation rates and favor the recognition of weaker consensus sequences for splicing factor (de la Mata et al., 2003). Such situation favors the usage of alternative splicing patterns and the outcome of splicing variated gene products.

Thus, the empirical support for the involvement of PQBP1 in X-LID via alternative RNA splicing is found to fit and complement diverse empirical findings and theoretical postulates independently reported by different research laboratories.

Please take a look at the image to the right and set your mind for speculation. The image was produced in Inkscape using one of the wonderful SVG templates from Wikipedia User 'Kelvinsong'.

Education

May 2010 – April 2011 |

Fellow scientific associate in “Penelope” (EU Marie Curie Research Training Network, MRTN-CT-2006- 0036076) coordinated by Dr. Luis Serrano, Centre for Genomic Regulation, Barcelona

July 2008 – April 2010 |

Fellow scientific associate in “Structure and Function of Membrane Receptors” (Collaborative Research Centre, SFB 449)

coordinated by Prof. Dr. Volker Haucke, Freie Universität, Berlin

Sept. 2003 – June 2004 |

Diploma thesis in the Systems Immunology Lab

led by Dr. M. Or-Guil at the Institute for theoretical Biology of the Humboldt Universität in collaboration with the Charité Universitätsklinikum, Berlin

Oct. 1998 – June 2004 |

Study of Biology with a Biochemistry major at the Humboldt Universität, Berlin

May 1996 – Sept. 1998 |

German as Foreign Language, German Literature and Philosophy, Epistemology, and Sociobiology as guest student at the RWTH, Aachen.

March 1979 – Dec. 1991 |

School in Viña del Mar, Chile and Philadelphia, PA, USA.

Publications

- 10 - M Spiess, E Verschueren, VE TAPIA, PM Kim, A Norgaard, C Landgraf, R Volkmer, F Hochstenbach, B Distel, B Winsor, L Serrano (2012). “EVOLUTION OF THE SH3 DOMAIN INTERACTOME ACROSS YEAST SPECIES”

- [Manuscript in preparation].

- 9 - Anna Ulbricht, Felix J. Eppler, VE TAPIA, Peter F.M. van der Ven, Padmanabhan Vakeel, Daniela Stadel, Albert Haas, Bernd Hoffmann, Paul Saftig, Christian Behrends, Dieter O. Fürst, Rudolf Volkmer, Waldemar Kolanus & Jörg Höhfeld. (2012) “CELLULAR MECHANOTRANSDUCTION RELIES ON TENSION-INDUCED AND CHAPERONE-ASSISTED AUTOPHAGY“

- [Manuscript submitted on June 29 2012]

- 8 - Volkmer, R & V Tapia. (2011) “EXPLORING PROTEIN-PROTEIN INTERACTIONS WITH SYNTHETIC PEPTIDE ARRAYS”. Mini-Reviews in Organic Chemistry 8(2): 164.

- 7 - Volkmer, R, I Kretzschmar & VE TAPIA. (2011) “Mapping receptor-ligand in-teractions with synthetic peptide arrays: Exploring the structure and function of membrane receptors”. European Journal of Cell Biology 91(4): 349.

- 6 - Tapia VE, Nicolaescu E, McDonald CB, Musi V, Oka T, Inayoshi Y, Satteson AC, Mazack V, Humbert J, Gaffney CJ, Beullens M, Schwartz CE, Landgraf C, Volkmer R, Pastore A, Farooq A, Bollen M, Sudol M. (2010) "Y65C MISSENSE MUTATION IN THE WW DOMAIN OF THE GOLABI-ITO-HALL SYNDROME PROTEIN PQBP1 AFFECTS ITS BINDING ACTIVITY AND DEREGULATES PRE-mRNA SPLICING." J Biol Chem.;285(25):19391-401. Epub 2010 Apr 21.

- This work explores the effect of a point mutation leading to X-LMR at the reductionist level of domain-peptide interactions, inferes potential affected functions, and tests inferences on pre-mRNA splicing.

- Download from JBC

- 5 - Mahrenholz CC, Tapia V, Stigler RD, Volkmer R. (2010) "A STUDY TO ASSESS THE CROSS-REACTIVITY OF CELLULOSE MEMBRANE-BOUND PEPTIDES WITH DETECTION SYSTEMS: AN ANALYSIS AT THE AMINO ACID LEVEL." J Pept Sci.;16(6):297-302.

- ever wanted to see if your favorite detection system reacts with cellulose-bound peptides? Well, chances are given that it is one of the three covered here: TAMRA-dye, luminol turn-over, and FITC

- 4 - Tapia VE & Volkmer R (2009) "EXPLORING AND PROFILING PROTEIN FUNCTION WITH PEPTIDE ARRAYS" in: Methods in Molecular Biology, Vol 570 (Eds. M Cretich & M Chiari). Humana Press. - ISBN: 978-1-60327-393-0.

- This work reviews the peptide array technology focusing on technological advancements, oriented immobilization of peptide probes, and some interesting applications. Going along the philosophy of the monography series, we give some general recomendations on methods and instruments. See the following newsletter comments by Tony Fong: Q&A: Raising the Profile of Peptide Arrays for Studying Protein Function, ProteoMonitor, August 13, 2009.

- View abstract at PubMed

- Read the newsletter by Tony Fong

- 3 - Tapia VE, Ay B, Triebus J, Wolter E, Boisguerin P, Volkmer R. EVALUATING THE COUPLING EFFICIENCY OF PHOSPHORYLATED AMINO ACIDS FOR SPOT SYNTHESIS. J Pept Sci. 2008 Dez ;14(12):1309-1314. - PMID: 18816512.

- This work was carried out to adapt "building block" approaches for the generation of phosphopeptides through resine-supported solid-phase peptide synthesis to the spot-technology, which relies on cellulose as support. It compares different coupling strategies for the incorporation of protected phoshoaminoacids into determined positions of synthetic peptides. We find that the use of EEDQ as coupling activator is the most efficient strategy in our comparison.

- view abstract at PubMed

- 2 - Tapia VE, Bongartz J, Schutkowski M, Bruni N, Weiser A, Ay B, Volkmer R, Or-Guil M. AFFINITY PROFILING USING THE PEPTIDE MICROARRAY TECHNOLOGY: A CASE STUDY. Anal Biochem. 2007 Apr 1;363(1):108-118. - PMID: 17288979.

- This work analyses the predictive potential of microarray-based binding assays. Fluorescent SI-measurements were used to fit a mass-action derived model estimating the observed affinity (equil. diss. const.).

- View abstract at PubMed

- 1 - Weiser AA, Or-Guil M, Tapia VE, Leichsenring A, Schuchhardt J, Frommel C, Volkmer-Engert R. SPOT SYNTHESIS: RELIABILITY OF ARRAY-BASED MEASUREMENT OF PEPTIDE BINDING AFFINITY. Anal Biochem. 2005 Juli 15;342(2):300-311. - PMID: 15950918.

- This work analyses the quantitative potential of measurements derived from peptide macroarray-based immunobinding assays. Chemoluminiscent signal intensity data was confronted with independent "golden stardard" measurements (surface plasmon resonance-based binding assays on a BIAcoreX maschine).